Red Flags

Serious medical conditions that can rapidly deteriorate and require urgent medical attention.

The information provided in this section has drawn largely upon resources for adults with SCI, whilst it may be useful for children with SCI and children and adults with SB, additional resources will be necessary to identify and respond to potential red flags for these clients.

Persistent Autonomic Dysreflexia

Autonomic Dysreflexia is a potentially life threatening condition in which blood pressure rises rapidly in response to a noxious stimulus below the level of SCI. It requires urgent attention.

Autonomic Dysreflexia - clinical presentation and management

Clinical presentation and management

Definition

Autonomic dysfunction (AD) occurs in people with spinal lesions at or above the T6 level only with rare occurrences below that spinal level. In response to a noxious stimulus below the level of SCI, autonomic dysreflexia may occur where the blood pressure rises rapidly – this is a medical emergency that needs immediate attention.

Clinical Presentation

- Pounding headache

- Elevated blood pressure (>20-40mmHg person’s normal BP*) NB: *baseline BP is often low in a person with high level paraplegia / tetraplegia (e.g. 90-100/60 mmHg).

- Bradycardia.

- Blotchy red rash above level of SCI

- Sweating above level of SCI.

- Nasal congestion.

- Pallor, goose flesh below level of SCI.

- Shortness of breath, apprehension/anxiety

Assessment

- Compare the person's current BP to their normal BP.

- Assess for cause of AD – look for noxious stimuli below the level of SCI (e.g. blocked catheter, wound deterioration).

- Refer to AD Treatment Algorithm for detailed assessment, treatment and management.

Treatment

- Treat episode of AD – remove the cause where possible, monitor BP and administer medication to lower BP if required.

- Refer to AD Treatment Algorithm (above).

Sepsis

Signs and symptoms of sepsis may be masked due to dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system in people with high thoracic or cervical SCI. For example, raised heart rate response may not be seen and postural hypotension, cold peripheries and loss of sweating below lesion level may be ‘normal’ for the person with SCI. There is a need to be particularly vigilant.

SEPSIS - clinical presentation and management

Clinical presentation and management

Definition

Sepsis occurs as the body’s systemic response to infection. It can escalate rapidly and cause organ failure and death.

Early recognition of signs of infection and increased systemic response are crucial.

After SCI, symptoms such as pain or early indication of infection may be impaired due to reduced sensation.

Infection may begin as localised infection of the pressure injury or wound, or other sites such as a bladder infection or chest infection/pneumonia.

Risk of developing sepsis may be elevated after SCI particularly with immune compromise and / or extensive paralysis.

Clinical Presentation

- Signs or symptoms of infection (e.g. wound infection or cellulitis; cough and/or distress of breath and easy fatigue; cloudy, bloody urine; increased spasticity or neuropathic pain).

- Chills and/or rigors.

- Rapid rise in temperature >38.3℃.

- Raised respiratory rate > 20 breaths/minute / raised heart rate or bradycardia.

- Confusion, anxiety, lethargy, clouded consciousness.

- Severe hypotension.

- Pale, cold, clammy (sluggish capillary return).

- Elevated blood sugar (without diabetes).

- Lowered temperature <36℃

Assessment

- Referral for medical assessment is urgently required if sepsis is suspected.

- Refer to Sepsis Pathway, available on the Clinical Excellence Commission Sepsis Kills page.

- Assess vital signs: Temperature, heart rate, blood pressure, respiratory rate

Other conditions with potential for rapid clinical deterioration that require immediate referral include the following:

Severe Malnutrition

Malnutrition is linked to poor wound healing and altered immune response, as well as being an independent risk factor for pressure injury development.

Malnutrition - clinical presentation and management

Clinical presentation and management

Definition

Malnutrition is defined as ‘a state of nutrition in which a deficiency or excess (imbalance) of energy, protein, and other nutrients causes measurable adverse effects on tissue/body form (body shape, size and composition) and function and clinical outcomes55.

Screening

Screening for malnutrition is an integral component of the PI Risk Assessment process. The Malnutrition Screening Tool (MST) either as a stand alone tool or performed as part of the Waterlow Score, should be performed by a member of the treating team. Scores ≥ 2 indicate the need for a dietitian referral for comprehensive nutritional assessment as soon as possible.

The MST identifies malnutrition in the general population, and the Spinal Nutrition Screening Tool (SNST) is a sensitive and condition-specific malnutrition screening tool that may be a useful alternative to MST in identifying people with SCI at risk of malnutrition.

Other screening tools include; Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA) / Mini Nutritional Assessment – Short Form (MNA-SF) as recommended by Trans Tasman Dietetic Group PI guidelines for those > 65 years. However at this stage the reliability and validity of the MNA in the SCI population is unclear.

Assessment

- Comprehensive nutritional assessment by a Dietitian is required if MST ≥ 2, unintended weight loss has occurred (i.e. >5% in 30 days or >10% in 180 days (NPUAP, EPUAP, PPPIA)) and the person has a Stage 3, 4, Unstageable or Suspected Deep Tissue Injury.

- Assessment should also include % unintentional weight loss over recent period of time.

- Assessment may include weight, diet history, food intake measures, 24-hour recall, anthropometry, biochemistry and BMI. BMI is not necessarily an accurate measure of nutritional status in people with SCI due to a number of factors including loss of muscle mass due to muscle paralysis and increased proportion of adipose tissue. Proposed adjusted BMI cut-off of 22kg/m2 for obesity for those with SCI.

- Food chart or observed intake may be assisted by nursing staff and other members of the health care team, however, the dietitian is required to estimate caloric needs, protein, and fluid requirements and create a diet plan.

- A validated nutritional assessment tool appropriate for the population should be used (where possible).

Investigations

- Nutrition and hydration related blood work (complete blood count, WCC, electrolytes, creatinine, urea, albumin, pre-albumin, C-reactive protein, total protein, transferrin, cholesterol, haemoglobin, vitamin B12, iron profile, folate).

- Blood glucose measures, total lymphocyte count, haematocrit.

- Indicators of inflammatory response are traditionally used as indicators of malnutrition i.e. Albumin, pre-albumin, but should be interpreted with caution due to the possible confounding effects of inflammation, renal function or hydration on these biomarkers.

Reference

Referral

- Referral to an accredited practicing dietitian for comprehensive assessment and nutritional support. Go to Dietitians Association of Australia

- Referral to tertiary Spinal Cord Injury services, including specialist spinal and wound dietetic services is strongly recommended for people with suspected malnutrition.

Reference

55.Waterson et al 2009

Multiple pressure injuries

The presence of multiple pressure injuries limits wound management and positioning options, potentially jeopardising intact skin, increases risk of infection and causes significant nutrient and fluid loss from the wounds.

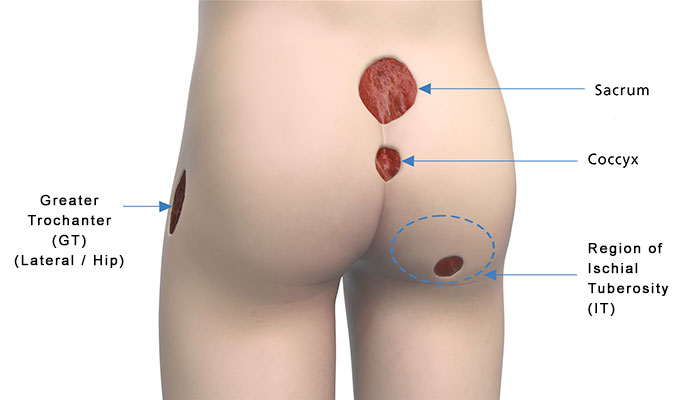

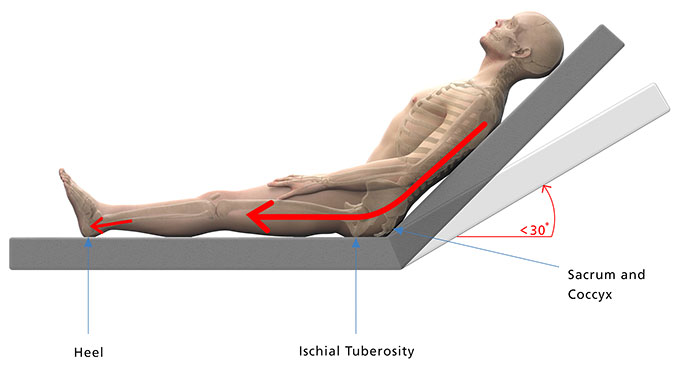

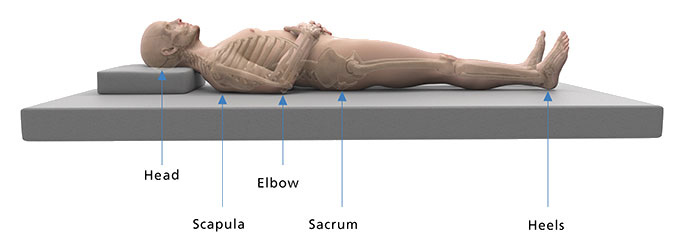

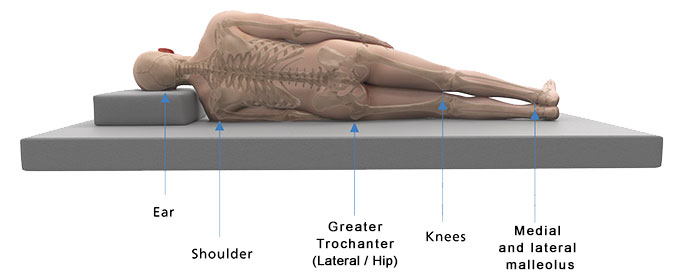

Advise clients and carers to monitor all at-risk areas and bony prominences. A position change every 2 hours is ideal. See the Management section of this toolkit for more information about bed rest and positioning.

Multiple pressure injuries - clinical presentation and management

Clinical presentation and management

Definition

The presence of pressure injuries at multiple (two or more) sites increases the complexity of care and indicates a failure of current pressure redistribution strategies. In a situation where there are multiple pressure injuries, early tertiary referral is strongly recommended.

Clinical Presentation

Person presents with multiple pressure injuries / wound sites.

|

|

|

|

Assessment

Assess each wound in detail and accurately identify the features of each pressure injury, including:

- Location

- Size

- Stage

- Peri-wound condition and wound edges

- Sinus tracts, undermining or tunnelling

- Exudate, colour and odour.

Refer to Wound Assessment section of this Toolkit

Investigations

- Wound swab, MCS.

- X-ray, CT or ultrasound may be required.

Levine method swab culture32:

- Cleanse wound with normal saline.

- Remove/debride nonviable tissue.

- Wait 2-5 minutes.

- If ulcer is dry, moisten swab with sterile normal saline.

- Culture the healthiest looking tissue in the wound bed.

- Do not culture exudate, pus, eschar or heavy fibrous tissue.

- Rotate the end of the sterile alginate-tipped applicator over a 1cm2 area for 5 seconds.

- Apply sufficient pressure to swab to cause tissue fluid to be expressed.

- Use sterile technique to break tip of swab into collection device designed for quantitative cultures.

Referral

- Referral to tertiary Spinal Cord Injury services is recommended for people with multiple pressure areas.

- Consider use of nutritional supplements to support increased protein requirements during healing.

Reference

32. NPUAP et al 2014 p. 164

Deep Wound Infection

Evaluate the pressure injury for clinical signs of superficial or deep infection.

In circumstances where the wound is deteriorating or the wound fails to progress in an expected timeframe, investigate for:

- Deep wound infection

- Osteomyelitis (bone infection)

- Possible presence of biofilm

Deep Wound Infection - clinical presentation and management

Clinical presentation and management

Symptoms and signs of clinical deterioration with possible development of a deep wound infection or abscess, complicating healing of a pressure injury wound, may include systemic symptoms (eg. Fever, chills, malaise) and local signs, such as increased wound size and depth, purulence with increased pus or drainage from wound fluctuance, crepitus, devitalised tissue, worsening swelling, spreading cellulitis or malodour. In a person with a spinal cord injury these may be associated with increased neuropathic pain, autonomic dysreflexia or worsening spasm.

Similarly, underlying bone infection may present with general symptoms, such as fever, nausea, fatigue as well as local redness, warmth and swelling and prevent wound healing or cause recurrent wound breakdown. Osteomyelitis may be present if there is exposed bone, if the bone feels rough or soft or the wound has failed to heal despite appropriate treatment. The wound is unlikely to heal permanently if osteomyelitis is not controlled.

When a wound has delayed healing and fails to respond to standard wound care or antimicrobial therapy, a biofilm may be present. Biofilms produced by microorganisms protect bacteria by making them resistant to conventional therapies and to culture, and reduce host defences and the effects of antimicrobials. Bacteria produced by biofilms may lie dormant for long periods of time and are frequently responsible for recurrent infections after repeated antibiotic therapy. The majority of biofilms can (and often do) slowly debilitate their hosts unless the infections are surgically removed. Biofilms can only be seen by the ‘naked eye’ if left undisturbed for a period of time, then they can appear as a slimy gel-like film11.

Assessment20

The bacterial burden of a wound may prevent a chronic wound from healing. The following tool can be used as a guide for deep and surrounding wound compartments for signs of infection

3 or more = high bacterial population in superficial wound compartment | 3 or more = high bacterial population in deep & surrounding wound compartments | ||

|---|---|---|---|

N | Non-Healing | S | Size increasing |

E | Exudate Increasing | T | Temperature increasing |

O | Os probing to exposed bone | ||

R | Red, friable granulation tissue | N | New or satellite wounds |

D | Debris or dead cells on wound surface | E | Erythema / Oedema |

E | Exudate increasing | ||

S | Smell | S | Smell |

If infection can be excluded, re-assess mechanical contributing factors such as forces associated with unrelieved sitting and transferring. Also, consider issues such as the weakness of scar tissue, malnutrition and incontinence as factors that may be contributing to deterioration or failure of chronic pressure injury wound healing.

Investigations

If osteomyelitis is suspected, investigation may include a plainxray, blood tests (WCC, ESR, C-RP), bone Scan, MRI or bone biopsy and advice from the Spinal Cord Injury Pressure Care Services is recommended. Bone scans can have high false-positive rates and an MRI scan may be preferred due to having higher diagnostic sensitivity and specificity20.

Management

Antibiotics are used to treat most wound infections. Surgery may be necessary to remove necrotic tissue near or surrounding infected area of wound, remove infected bone and drain any abscesses, or pockets of pus. To remove biofilm, vigorous physical cleansing or debridement by an appropriately qualitied professional is usually required. The results of deep tissue culture and histopathology of bone biopsy will dictate the length of antibiotic treatment.

Referral

Consultation with tertiary Spinal Cord Injury services is strongly recommended for patients with suspected deep wound infection, osteomyelitis or possible biofilm.

Reference

11.Consortium of Spinal Cord Medicine 2014 p.31

20.Woo and Sibbald 2009 as cited in Houghton et al 2013 p.157

3.Houghton et al 2013 p. 179.