Pressure Injury and Spinal Cord Injury

More than 85% of people with SCI and SB will develop a pressure injury (PI) in their lifetime. At any one time, more than 30% of people with SCI and SB in Australia have a pressure injury. The prevalence rate in adults with SB is estimated to be 34%26. The social and economic impact of PI on the individual, family and community is immense and can have long term physical and psychological consequences.

SCI and SB-specific factors amplify risk

SCI and SB -specific factors amplify risk

SCI and SB-specific factors amplify risk

SCI and SB-specific risk factors increase exposure to extra pressure or reduce the skin’s ability to tolerate pressure.

Pressure

As a result of a SCI or SB, people are more susceptible to the effects of direct pressure due to: (i) impaired or absent protective sensation below the level of injury (e.g. loss of pain, temperature, pressure and light touch sensation), (ii) muscle paralysis which limits mobility, ability to transfer and re-distribute body weight, often requiring a wheelchair or assistive device and, as a result, (iii) significant limitations to functional activity.

Extrinsic Factors

Extrinsic factors reducing tissue tolerance for people with SCI or SB include: (i) increased moisture from hyperhidrosis, long periods of sitting or from possible bladder or bowel incontinence; (ii) friction from reduced clearance during transfers, poorly fitting equipment or clothing; and (iii) shear from sliding down the bed, reduced lift or clearance when re-positioning, muscle spasticity or sliding forwards in a poorly set-up wheelchair.

- Moisture

- Friction

- Shear

Intrinsic Factors

Intrinsic factors reducing tissue tolerance for people with SCI or SB include: (i) impaired circulation from autonomic nervous system and cardiovascular changes, and, decreased muscle pump reducing venous return and the delivery of oxygen to the muscles; (ii) use of medications that reduce alertness; (iii) increased risk of malnutrition; (iv) high prevalence of comorbidities and other chronic diseases; and (v) secondary conditions such as shoulder pain reducing the ability to lift and transfer body weight during daily mobility and self-care activities.

- Oxygen delivery

- Medications

- Demographics

- Nutrition

- Chronic illness

- Pain

- Skin

- Temperature

Braden & Bergstrom (1987)

Spinal cord injury-specific factors amplify pressure injury risk.

Psychosocial and lifestyle factors contribute significantly to PI development and the success of the management plan.

Lifestyle factors

This table23 can be used by health professionals and consumers to explain pressure injury development and target risk factors. Information is based on results from the University of Southern California (USC) and Rancho Los Amigos National Rehabilitation Center (RLANRC)’s Lifestyle Redesign® for Pressure Ulcer Prevention in Spinal Cord Injury project.

| FACTOR | EXPLANATION |

|---|---|

| Perpetual danger | Even when an individual implements preventive strategies, unforeseen circumstances may trigger pressure ulcer development. |

| Change or disruption of routine | Development of a pressure ulcer may sometimes be traced to a single change that disrupts the existing risk equilibrium and produces a cascade of events. |

| Decay of prevention behaviours | Distractions, forgetfulness, and other factors may reduce the frequency of performing prevention techniques, often without the individual even recognising it. |

| Lifestyle risk ratio | This is the impact of the sum of physical or lifestyle liabilities, such as poor nutrition and inadequate finances, and buffers, such as a good support system and adherence to preventive strategies. |

| Individualisation | The unique balance of risk and prevention factors at any given time for each person with spinal cord injury determines pressure ulcer development. |

| Simultaneous presence of prevention awareness and motivation | Long-term prevention knowledge, short-term attention to the situation, and adequate motivation to perform the strategies must all be present to prevent pressure ulcer development. |

| Lifestyle trade-off | The ways in which an individual balances the needs to engage in personally meaningful activities and to use rest and caution to prevent pressure ulcers change the risk balance. |

| Access to needed care, service, and supports | The inability to obtain appropriate services, for various reasons, at the time they would be most beneficial or necessary increases pressure ulcer risk. |

Reference

1.Jackson et al 2010

Assessment of ongoing pressure injury risk

Use the results of a comprehensive and systematic assessment of pressure ulcer risk factors to select and implement risk management strategies in individuals with spinal cord injury.20

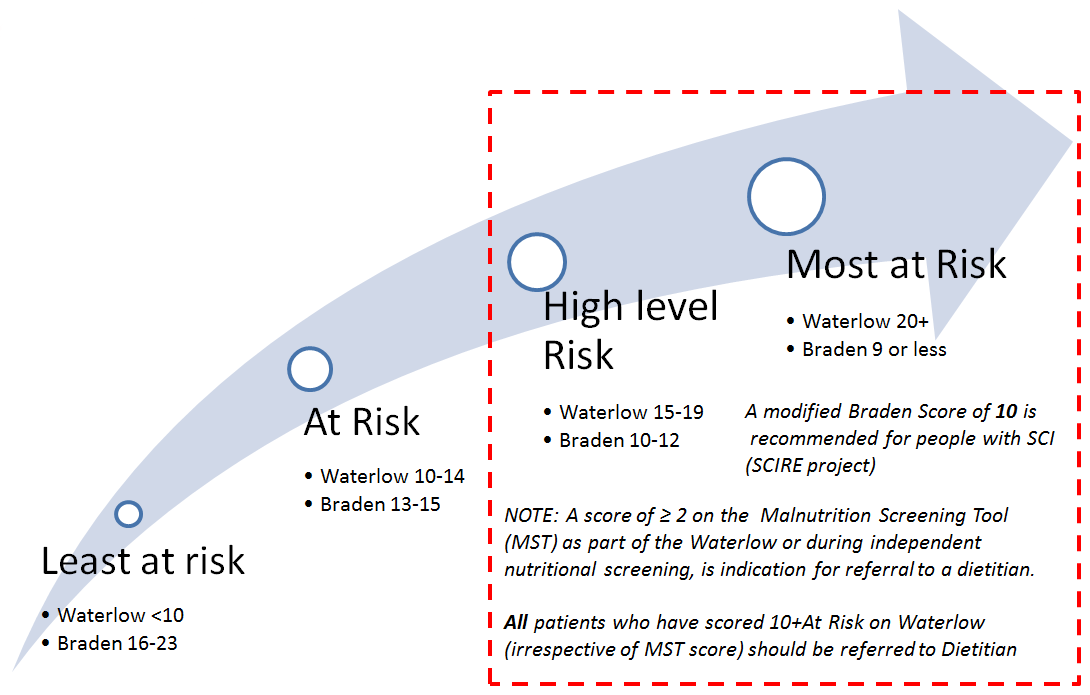

All people with SCI and SB are at high risk of developing pressure injuries. There is no SCI and SB -specific PI risk assessment that has demonstrated reliability with this population. Currently the Braden Scale or the Waterlow Scale are most commonly used.

Braden Scale and the Waterlow Scale

All people with SCI and SB are at high risk of developing pressure injuries. Until a reliable and consistent SCI and SB -Specific pressure injury risk assessment is developed the Braden Scale or the Waterlow Scale is recommended.

Clark et al (2006) 9 describe a person’s risk profile in terms of interacting physical, mechanical, health-behaviour, psychological, social and environmental liabilities and buffers.

Risk stratification may be useful prior to a comprehensive assessment of cause and contributing factors.

Risk stratification

PERSONAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL CHARACTERISTICS

Risk may be further stratified based on a range of factors.

| Protective Factors | High Risk | Most at Risk |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Using the following references, proposed risk stratification is presented; NSW State Spinal Cord Injury Service Model of Care for Prevention and Integrated Management of Pressure Injuries in People with Spinal Cord Injury and Spina Bifida, Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine Pressure Ulcers Prevention and Treatment Following Spinal Cord Injury, Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation Evidence: Pressure Ulcers, Canadian Best Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Management of Pressure Ulcers in People with Spinal Cord Injury).

References

9. Clarke, F., Jackson, J., Scott, M., Carlson, M., Atkins, M., Uhles-Tanaka, D. & Rubayi, S. (2006) Data-based models of how pressure ulcers develop in daily –living contexts of adults with spinal cord injury. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 87, 1516-1525

20. Houghton PE, Campbell KE & CPG Panel (2013). Canadian Best Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Management of Pressure Ulcers in People with Spinal Cord Injury. A resource handbook for clinicians.

23. Jackson J, Carlson M, Rubayi S, Scott MD, Atkins MS, Blanche EI, Saunders-Newton C, Mielke S, Wolfe MK & Clark FA. (2010). Qualitative study of principles pertaining to lifestyle and pressure ulcer risk in adults with spinal cord injury. Disabil Rehabil. 32(7), 567-78. doi: 10.3109/09638280903183829.

26. Kim S, Ward E, Dicianno BE, Clayton GH, Sawin KJ, Beierwaltes P, Thibadeau J (2015). Factors Associated With Pressure Ulcers in Individuals With Spina Bifida. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 96(8) 1435-1441

47. The Children’s Hospital at Westmead, Sydney Children’s Hospital, Randwick and Kaleidoscope Children, Young People and Families (2018 p.1). Sydney Children’s Hospital Network FACTSHEET: Hydrocephalus and Spina Bifida