Pleural effusion

Pleural effusions are collections of fluid between the parietal and visceral pleura caused by a disruption of the homeostatic forces that control normal flow.

Under normal circumstances the space has a small amount of lubricating fluid present to allow the lung surface to glide within the thorax during the respiratory cycle. Approximately 15 mL/day of fluid enters this potential space, primarily from the capillaries of the parietal pleura. This fluid is then removed by the lymphatics in the parietal pleura.

At any one time there is about 20 mL of fluid in each hemithorax giving rise to a layer of fluid 2 to 10 mm thick. This regulated fluid balance is disrupted when local or systemic derangements occur and this leads to characteristic changes in fluid protein and LDH composition helping to identify the underlying cause. The list of pleural effusion causes is extensive. In clinical practice the commonest are congestive cardiac failure, pneumonia and malignancy.

Symptoms can be variable and can include shortness of breath, cough and pleuritic chest pain. Massive pleural effusions may produce significant cardiorespiratory compromise requiring urgent attention in ED, however, the majority are asymptomatic or produce minimal symptoms. The aetiology of the pleural effusion determines other associated signs and symptoms.

Features of examination can include hypoxia, reduced air entry on the affected side, reduced vocal fremitus and resonance and a stony dull percussion note. A pleural rub is only present in small effusions

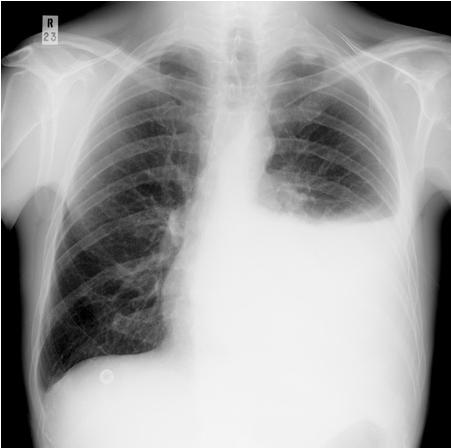

Investigations should start with a CXR although this will only show an effusion of >200 mL of fluid. Effusions can be seen earlier in lateral CXRs with just 50ml causing blunting of the costophrenic angles. A thoracic ultrasound scan can estimate effusion size and is useful in thoracentesis direction, increasing success rates and reducing complications. An additional benefit of ultrasound is in detecting pleural fluid septations with more sensitivity than CT. CT scans should be performed in the investigation of all undiagnosed exudative pleural effusions and can be useful in distinguishing malignant from benign pleural thickening. They are useful in estimating size, loculation and confirmation of additional pathology e.g. tumour.

Ascertaining the aetiology of the pleural effusion is an important step in the ED assessment as this helps to direct the appropriate treatment. Along with a directed history, examination and imaging, a diagnostic pleural tap is sometimes, but not universally, required to formally evaluate the fluid. The gross fluid appearance can guide more detailed investigations alongside standard laboratory analyses which include biochemistry, cytology, and culture. The British Thoracic Society (BTS) guidelines recommend against aspirating bilateral pleural effusions strongly suggestive of a transudate unless there are atypical features or they fail to respond to therapy.

Therapeutic thoracentesis is sometimes indicated in those with moderate to large pleural effusions for alleviation of dyspnoea and cough