Paediatric patients

For paediatric guidelines refer to:

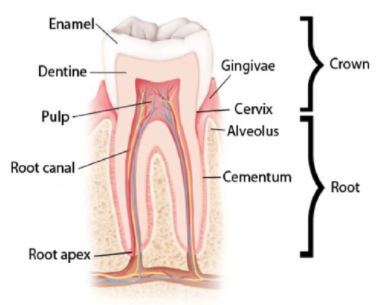

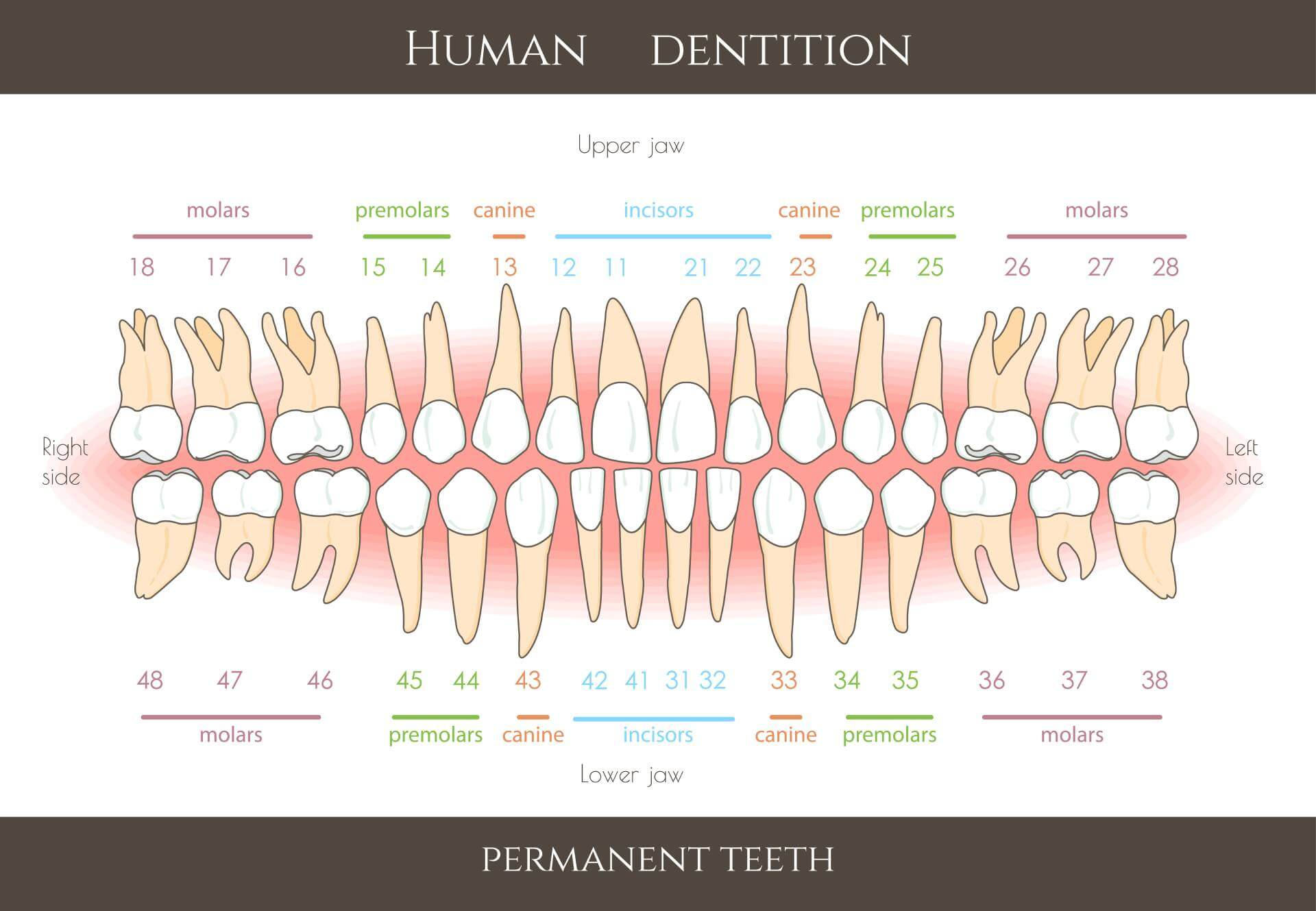

Tooth anatomy

Teeth have three layers: enamel, dentine and pulp.

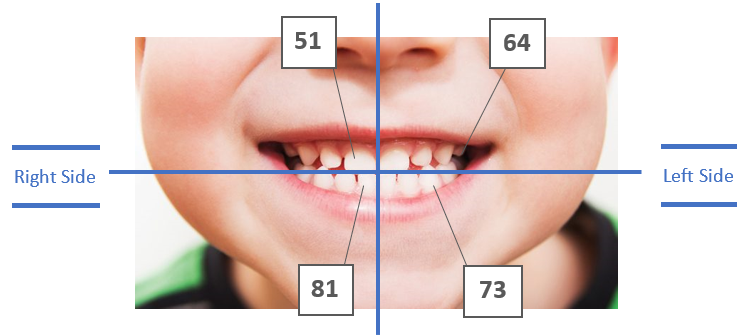

Primary teeth

20 small, very white, bulbous crowns, often worn with flat edges. Teeth are identified by two numbers, for example: 52.

The first number indicates the quadrant in the mouth, the second number indicates the tooth number, counting from the midline of the face, towards the back of the mouth.

Mixed dentition

Children will usually present with a mixed dentition between the ages of 6–12 years old. It is important to identify if the presentation is associated with a permanent or primary tooth.

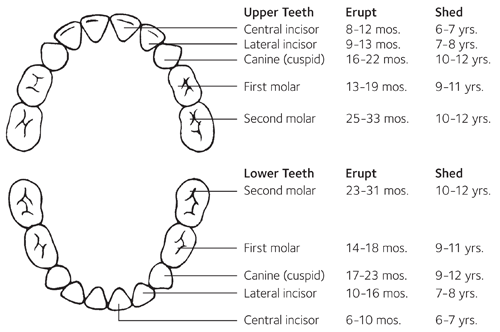

Average age when primary teeth are lost:

- Incisors: 5–8 years old

- Canines and molars: 9–12 years old

- Usually begin to appear in the mouth from 6 years of age

- Teeth are identified by two numbers, for example: 25

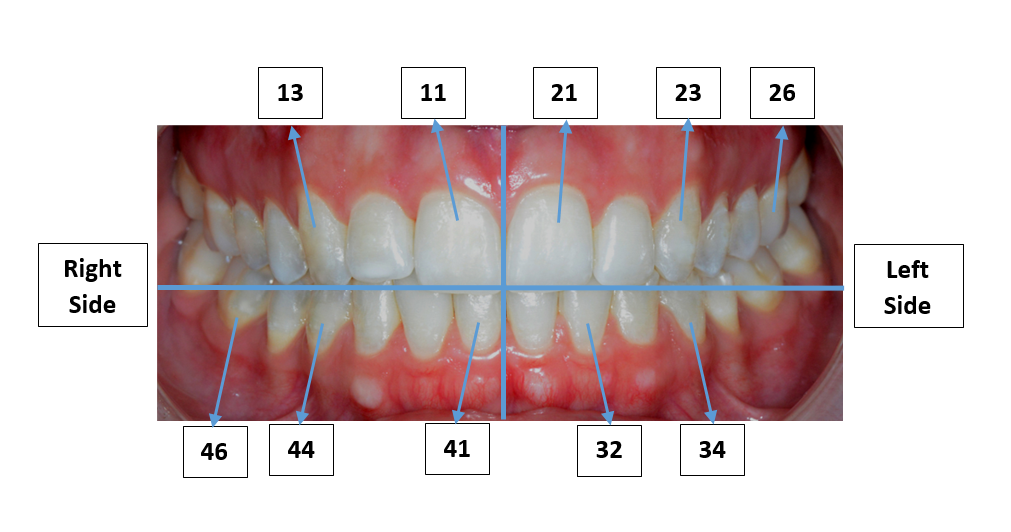

Permanent teeth

32: larger, creamier colour, jagged edges on newly-erupted teeth.

The first number indicates the quadrant in the mouth, the second number indicates the tooth number, counting from the midline of the face, towards the back of the mouth.

When describing the tooth use the FDI (International Dental Federation) system (above). However, if you are unable to identify the specific tooth number, use a description such as:

- upper or lower

- left or right

- tooth type (if known), e.g. upper right canine.

Dental conditions - non trauma

Key points

- Opportunistic education for families on good oral hygiene practices and how to access dental services can prevent dental caries (tooth decay).

- Once a dental abscess or infection has formed, extraction or root canal therapy is usually required to remove the source of the infection.

- Submandibular infection should be considered as differential diagnosis of oral pain.

Background

- Dental caries occurs in more than 40% of Australian children and can begin as soon as teeth erupt during infancy.

- Routine dental care should be provided in the community rather than by hospitals, except for patients with chronic illness that may be impacted by dental caries, e.g. cancer, cardiac disease, immunodeficiency, bleeding disorders, special needs, or where general anaesthetic is required.

Assessment

Dental history

- Frequency, duration and who performs tooth brushing

- Exposure to sugary and high acidity foods and drinks (including processed fruit juice and cordial)

- Previous dental review and advice given

- Previous dental trauma

- Dental or facial pain

- Chronic conditions which may impact saliva production or swallowing

- Consider non-dental causes, e.g. cervical lymphadenitis, parotitis, submandibular infections

- Dental pain is often acute, unliteral, and mostly localised in the mouth. It can be exacerbated by chewing, biting, or thermal stimuli, and can present with swelling.

Examination

Lift the lip to ensure thorough examination of upper front teeth and gums, and:

- check for loose or tender teeth.

- look for early signs of decay including white or brown spots or lines along the top of the tooth, adjacent to the gum line, which don’t brush off

Abscess may be indicated by:

- fever and systemic symptoms may be absent

- trismus

- erythema and cellulitis of facial skin overlying tooth, submandibular or periorbital

- tender gingival swelling or erythema

Investigations

- Blood tests are not required unless systemic symptoms present.

- Consider orthopantogram to assess for evidence of abscess.

Treatment

General principles

- Provide adequate analgesia

- Dental abscess usually involves tooth extraction with incision and drainage

- Definitive treatment of the carious tooth will still be required after treatment of pain and infection

Further management principles for common dental conditions

Abscess

Dental – most commonly caused by advanced tooth decay.

Periodontal – pain caused by an acute infection that originates from a localised area of severe periodontal disease.

May require drainage to relieve the pain

Antibiotics if systemic infection, immunocompromise, or delay to more definitive treatment

Post extraction bleed

It is normal for there to be small amounts of ooze for up to 12 hours post extraction.

- Place pressure by using gauze.

- Administer local anaesthesia if required and apply pressure to the wound for 5-10 minutes.

- If bleeding persists, rinse socket with saline, soak gauze with tranexamic acid, place gauze in extraction site and ask the patient to bite firmly on gauze for 30 minutes.

- If the area is still bleeding, pack the extraction site with absorbable gelatine sponge, and suture into position with 4.0 silk suture.

- Re-examine after five minutes to confirm the haemostasis.

Post extraction pain

This type of pain usually occurs within 24 hours after a tooth extraction.

Oral analgesia.

Alveolar osteitis

‘Dry socket’ is a condition that may occur post-extraction. It occurs when a blood clot is inadequate, or broken down due to inflammation, or further trauma post extraction.

- Occurs 2-3 days post tooth extraction

- Pain may radiate to the ear

- Necrotic debris may be present in socket

- Malodorous breath

The condition is usually self-limiting within 2-3 weeks and is more commonly seen in the lower jaw and among patients who smoke.

- Irrigation of the socket (chlorhexidine or warm saline to remove the debris).

- Dress the socket with bismuth iodoform paraffin paste, lidocaine gel on ribbon gauze to protect the stimuli.

- Oral analgesia.

- Antibiotics – if pus in the socket or swelling in the area.*

* Note that dry sockets are not a bacterial infection, thus antibiotics are not usually required in the absence of pus or swelling.

Other dental conditions

Tooth decay (dental caries)

Tooth decay is a preventable disease caused by increased acid in the oral environment which attacks the tooth surface causing cavitation. Left untreated, tooth decay can cause pain, infection and tooth loss.

Gum disease

Gingivitis is a preventable, reversible inflammation of the gingivae (gums) caused by poor oral hygiene. It results in gingival tissues that bleed very easily when brushed. Periodontal disease occurs when gingivitis has progressed to involve the deeper soft tissues and supporting alveolar bone. Periodontitis is progressive and can lead to localised infection and eventual tooth loss. This disease usually progresses without symptoms, however there may be localised acute infections that may cause acute pain resulting in presentations to emergency departments (EDs).

Submandibular infections

Submandibular infection should be considered as differential diagnosis of oral pain. It is defined as cellulitis of sublingual or submandibular area and may be either unilateral or bilateral. This cellulitis may cause an obstruction to the airway (Ludwig’s angina) or systemic sepsis.

Symptoms associated with submandibular infection can include:

- submandibular pain

- swelling

- trismus

- inability to protrude tongue

- drooling

- dysphagia

- dysphonia and dyspnoea are late signs.

If the patient presents with a dental infection that poses a risk of airway obstruction, they may need intravenous (IV) antibiotics and/or surgical drainage.

Antibiotics

Indications:

- Adult teeth that have been replanted.

- Where the patient has systematic signs of infection (fever, malaise, lymphadenopathy, trismus), has compromised immunity, or is at risk of the progressive and rapid spread of infection (cellulitis or Ludwig’s angina).

Antimicrobial recommendations may vary according to local antimicrobial susceptibility patterns. Refer to local guidelines or Therapeutic Guidelines: Acute odontogenic infections (login required) for more information.

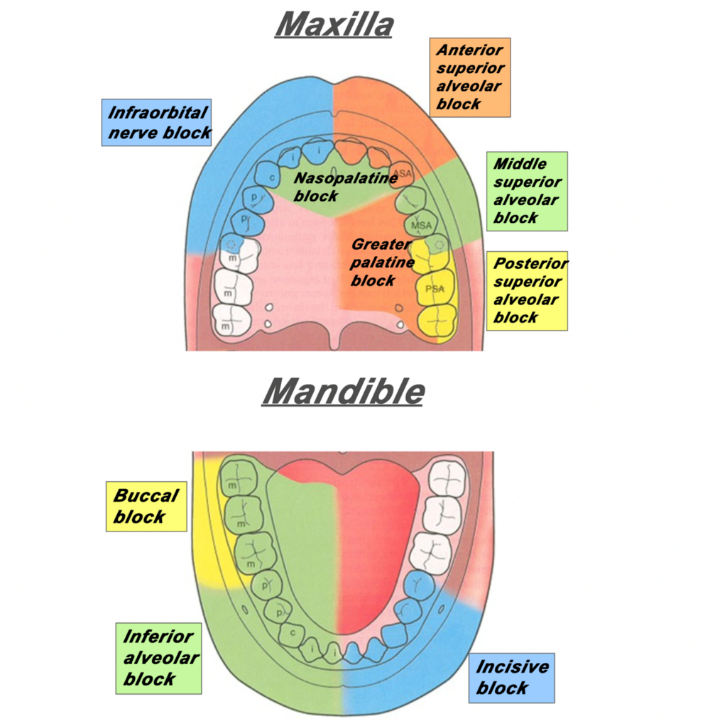

Anaesthetic

Administration of local anaesthetic is effective for the initial management of severe pain, alongside oral analgesics.

Topical local anaesthetics (2% lignocaine gel) can also be effective for temporary pain relief for oral ulcerations. It can also be applied prior to the provision of anaesthetic.

After the administration of local anaesthesia, patients should be told to be careful about biting the numb areas of their mouth and lip.

The following provide links to a demonstration of achieving anaesthesia to the areas of the dentition:

Note: Adequate training should be completed before administering anaesthesia.

Dentist consultation

Consultation with a dentist should be considered if there is:

- fever in setting of suspected dental abscess

- facial cellulitis or swelling.

Transfer

A transfer should be considered if specialist dental or maxillofacial assessment and management is required and is not locally available.

Additional information

- Infiltration (video)

- Inferior alveolar injection (video)

- Mandibular anaesthesia (video)

- Maxillary anaesthesia (video)

- Inferior alveolar nerve block (video)

- Dental Emergency Presentation (e-learning)

A comprehensive, well referenced guide to dental emergencies - how to manage them in the ED, and how and when to refer for specialist treatment. - Emergency Department Dental Referrals (GL2023_005)

Source: NSW Health

Dental trauma

Key points

- Management of dental trauma depends on whether primary or permanent teeth are impacted. Primary teeth should not be replanted, adult teeth can be replanted.

- Successful replantation of permanent teeth or teeth fragments requires urgent management to improve long term tooth viability.

- For paediatric patients, see paediatric dental trauma (Royal Children's Hospital).

Background

- Dental trauma is very common, and often occurs alongside other injuries, especially facial and head injuries. Where required, perform a primary and secondary survey prior to instituting dental management.

- Healing after a dental injury requires good oral hygiene. Swabbing the area with 0.1% chlorhexidine twice a day for 10–14 days reduces the infection risk. A soft diet will also allow loose teeth to become firmer.

Assessment

History

- Mechanism of injury and associated injuries

- Time since injury – avulsion of a permanent tooth is a dental emergency (prognosis dependent on how swiftly the tooth is replanted into socket)

- Encourage recovery of avulsed tooth or tooth fragments

- First aid rendered (tooth rinsing, wet or dry storage)

- Sensitivity to hot and/or cold

- Previous dental history including injuries, crowns or prostheses

- Tetanus immunisation status

Examination

Examine the head, neck and inside the mouth for hard and soft tissue injuries.

- Symmetry in the mouth and teeth

- Lift the lips to look for gingival or oral mucosal injury

- Type of dental injury: loose or displaced tooth, fractured tooth, injury to supporting bone, injury to oral mucosa or gingivae

- Bite for even occlusion, subjective or objective; steps in bite or bone border

- Temporomandibular joint movement and tenderness

- Numbness, intra or extra-oral bruising

- Account for all lost teeth and fragments, examine chest and soft tissues of the mouth if any missing as they may have been aspirated or embedded

- Be aware of concomitant injuries including head injuries, e.g. concussion, facial fractures

Investigations

- Orthopantogram if considering fractured mandible, temporomandibular joint (TMJ) injury or concern for fully intruded tooth.

- Chest x-ray if it is suspected that a tooth has been aspirated.

Treatment

- Prophylactic antibiotics are not recommended if operative management is not required.

- Provide tetanus booster if required.

Further management principles for common injuries

Uncomplicated fracture

Fracture with no pulpal exposure

- Store the broken piece of tooth in water.

- If the tooth remaining in the mouth is sensitive, cover with a temporary filling material available in your department, e.g. Cavit or glass ionomer cement (GIC).

- Refer to a local dentist for further management.

Complicated fracture

Fracture with pulpal exposure

- Consider the use of local anaesthetic for symptomatic relief.

- Cover the exposed pulp with a small moist cotton gauze then cover with a temporary filling material, e.g. Coloplast.

- Refer to local dentist for further management.

Luxation

Teeth which are loosened, pushed in and moved

Initial considerations:

- Do not handle the tooth by the root surface.

- Consider antibiotic prophylaxis and a tetanus booster if the tooth has come into contact with soil.

- Notify the patient that a delayed replantation has a poor long‐term prognosis.

Management principles

- Move teeth gently back into their original position.

- Place gauze between upper and lower teeth.

- Refer to a local dentist for further management.

Avulsion

Where the tooth is knocked out

Initial considerations:

- DO NOT replant primary (baby) tooth.

To replant permanent (adult) teeth:

- Rinse the tooth with saline.

- Administer local anaesthetic.

- Replant tooth into socket gently.

- Apply a splint if comfortable doing so.

- Advise good oral hygiene, gentle brushing, and a soft diet for two weeks.

- Refer to local dentist for further management.

Dentist consultation

Consider consulting a dentist when there is trauma requiring surgical input and assessment.

Transfer

Consider transferring when specialist dental or maxillofacial assessment and management is required and is not locally available.

Emergency department dental referrals

Some patients presenting to the ED may be eligible for a referral to NSW public dental clinics. Use the statewide form Dental Referral for Emergency Departments to NSW Public Dental Clinics (NH606530A) to refer patients. Get copies of this form from Finsbury Green using your local process. The form is to be given to the patient on discharge.

Emergency Department Dental Referrals (GL2023_005) provides direction on making appropriate dental follow-up referrals from NSW hospital EDs.

Further resources

These resources require a log in. NSW Health staff can access them via the Clinician Access Information Portal (CIAP)

- Dental Trauma Guide

Resource Centre for Rare Oral Diseases and Department of Oral and Maxillo-Facial Surgery, University Hospital of Copenhagen - Maxillofacial Trauma: Therapeutic Guidelines

Further reading

- Bourguignon C, Cohenca N, Lauridsen E, et al. International Association of Dental Traumatology guidelines for the management of traumatic dental injuries: 1. Fractures and luxations. Dent Traumatol. 2020;36(4), 314-330. DOI: 10.1111/edt.12578

- Day PF, Flores MT, O'Connell AC, et al. International Association of Dental Traumatology guidelines for the management of traumatic dental injuries: 3. Injuries in the primary dentition. Dent Traumatol. 2020;36(4), 343-359. DOI: 10.1111/edt.12576

- Fouad AF, Abbott PV, Tsilingaridis G, et al. International Association of Dental Traumatology guidelines for the management of traumatic dental injuries: 2. Avulsion of permanent teeth. Dent Traumatol. 2020;36(4), 331-342. DOI: 10.1111/edt.12573

- Levin L, Day PF, Hicks L, et al. International Association of Dental Traumatology guidelines for the management of traumatic dental injuries: General introduction. Dent Traumatol. 2020;36(4), 309-313. DOI: 10.1111/edt.12574

- Therapeutic Guidelines. Acute odontogenic infections. Melbourne: Therapeutic Guidelines Limited; Dec 2019 [updated Mar 2021; cited 19 Jun 2024].

- Therapeutic Guidelines. Complications after oral surgery. Melbourne: Therapeutic Guidelines Limited; Dec 2019 [updated Mar 2021; cited 19 Jun 2024].

Accessed from the Emergency Care Institute website at https://aci.health.nsw.gov.au/networks/eci/clinical/tools/dental-emergencies