Lower Limb Injuries

Upper Leg

Knee

Lower Leg

Hip and Pelvis

Femoral Shaft and Distal Femur

Summary

Fracture Type | Management | Follow-up |

|---|---|---|

Femoral Shaft | Traction by device or skin traction if not provided pre hospitally Manage whole patient as per ATLS/EMST | As per orthopaedic admitting team |

Classification

Femoral Shaft

- Comminuted or not

- Cortical connection of note

- Spiral

- Transverse

- Overlap, off ending, shortening.

Distal Femur

Descriptive

- supracondylar

- intercondylar

- intra-articular

- extra-articular.

Epidemiology

Femoral Shaft

Younger: often high speed MVA or significant trauma mechanism, as part of polytrauma.

Older: Osteopenic, assess in the context of cause of fall.

May be associated NOF fractures and risk for bilateral in MVAs.

Distal Femur

As for shaft.

Presentation

Femoral Shaft

Symptoms, pain in thigh.

Physical exam. tense, swollen thigh, tender, shortened. Neurovascular examination recorded.

Distal femur

Pain and deformity, swelling around the knee. Risk for popliteal artery in displaced fractures.

Imaging

Femoral Shaft

- X-Ray:

- AP and lateral views of entire femur.

- AP and lateral views of ipsilateral hip and knee.

- CT: Rarely indicated.

Distal Femur

- X-Ray:

- obtain standard AP and Lat., traction views.

- AP, Lat, and oblique traction views can help characterise injury.

- CT:

- frontal and sagittal reconstructions.

- useful for:

- establishing intra-articular involvement.

- identifying separate osteochondral fragments in the area of the intercondylar notch.

- preoperative planning.

- Angiography

- ?indicated when diminished distal pulses after gross alignment restored.

ED Management Options

Femoral Shaft

Initial management as per ATLS/EMST considering potential polytrauma complications. Potential for blood loss into thigh being a significant contributor to shock.

Traction as per device often applied as pre hospital measure, assure has not lost traction or position in transit. Assess neurovascular status on arrival.

Most often operative intervention, but may be by long leg caste where non displaced and multiple medical conditions.

May transition to skin traction where operative intervention is not readily available.

Distal Femur

Whole patient management as above.

May be non-operative, mostly operative.

Referral and Follow Up Requirements

Fracture Type | Urgency | Follow-up |

|---|---|---|

Femoral Shaft | Immediate referral to orthopaedics | As per team |

Distal Femur | Non urgent review by orthopaedics, depending on other injuries | Possible outpatient management but most likely inpatient. Discuss all cases with ortho. |

Potential Complications

Nerve damage, blood loss from vascular damage. Not considering other trauma in polytrauma.

Patient Advice

As per orthopaedic team on discharge.

Further References and Resources

- Orthobullets - femoral shaft fractures

- Orthobullets - distal femur fractures

Femur Splints

There are a number of different femur splints available. These may be broadly grouped as ‘half ring’ splints (e.g. Donway, Thomas) and ‘non half ring’ splints (e.g. Sager or CT). NSW Ambulance use only the CT-6 splint (an advanced, lightweight form of traction splint).

Patients may arrive from the field with a splint attached. Remember that you should still be able to assess and monitor the neurovascular status of the leg, and remember to check for and regularly assess the skin for pressure sores from splint application.

You may transition to a different type of femoral splint once the patient arrives in the ED, pending your local protocols and the equipment available.

Appropriate splinting will assist with haemodynamic control as well as providing an analgesic affect, but remember that all patients with confirmed or highly suspected femoral fractures should have early consideration for regional analgesia (femoral nerve block, FNB or fascia iliaca block, FIB), upon arrival in the ED.

CT-6 Splint

The following video has been prepared by the Queensland Ambulance Service and demonstrates the correct application of the CT-6 Splint on an adult patient with a femoral shaft fracture.

The Donway Traction Splint

The following video has been prepared by the ECI and demonstrates the correct use of the Donway Femur Traction Splint.

Tibial Shaft Fractures

Summary

Fracture Type | Management | Follow-up |

|---|---|---|

Open Tibial Shaft Fractures | Washout in ED Long-leg cast Ice and elevation IVAbx | Will require admission for IVAbx, formal washout +/- fixation |

Closed simple tibial shaft fractures with none of the following:

| Long-leg cast Non-weight bearing Ice and elevation Monitor for acute compartment syndrome | May be suitable for orthopaedic review within 1-2 days but must be discussed with on-call orthopaedic team prior to discharge. |

All other closed tibial shaft fractures | Long-leg cast Non-weight bearing Ice and elevation Monitor for acute compartment syndrome | Orthopaedic review in ED |

Classification

There are many classification systems for tibial shaft fractures including:

Gustillo – grades 1-3. Describes the associated soft tissue injury in open fractures. This classification system is prognostic in terms of healing time and rate of nonunion.

AO classification – simple, wedge or complex fractures with subclassifications based on associated fibular fractures.

Tscherne Classification- describes closed fractures:

- Grade 0 - Injury from indirect forces with negligible soft tissue damage.

- Grade I - Closed fracture caused by low-moderate energy mechanisms, with superficial abrasions or contusions of soft tissues overlying the fracture.

- Grade II - Closed fracture with significant muscle contusion, with possible deep, contaminated skin abrasions associated with moderate to sever energy mechanisms and skeletal injury; high risk for compartment syndrome.

- Grade III - Extensive crushing of soft tissues, with subcutaneous degloving or avulsion, with arterial disruption or established compartment syndrome.

Epidemiology

- Estimated to be as high as 1/2,000 per annum

- Fractures often result in open injuries because of the minimal amount of subcutaneous tissue between it and the skin.

- Transverse shaft fractures typically result from a direct blow to the bone.

- Spiral fractures are the result of rotational forces.

- A comminuted fracture suggests the mechanism had a very high energy impact.

- Concomitant fibula fracture in up to 60% of cases.

- Significant osteoporosis increases risk of open or more complex fractures.

Presentation

- Localised pain

- Localised swelling or evidence of other soft tissue injury

- Inability to weight bear

- Altered alignment of lower leg may be present.

Imaging

- Plain film radiographs are considered highly sensitive and specific for detecting trauma related tibial shaft fractures.

- Detecting stress and insufficiency fractures on plain films is less sensitive.

ED Management Options

- Long-leg posterior splint from metatarsal heads to the upper thigh

- Knee in 10–15° flexion

- Ankle at 90°

- Non-weight bearing

- Ice and high elevation

- Analgesics

- Explain and monitor for signs of acute compartment syndrome

- Due to the significant risk of acute compartment syndrome associated with tibial shaft fractures, it is unlikely that a patient with a tibial shaft fracture will be discharged home from ED. Most patients will require admission for strict elevation, pain management, neurovascular monitoring +/- surgery.

- There may be limited cases where the most simple, non-displaced fractures may be suitable for discharge home from ED. However all tibial shaft fractures must be discussed with the on-call Orthopaedic team prior to such a decision being made.

Referral and Follow Up Requirements

Fracture Type | Urgency | Follow-up |

|---|---|---|

Open tibial shaft fracture | Will require admission | Review by orthopaedics in the ED |

Most closed tibial shaft Ffactures | Most likely will require admission | Review by orthopaedics in the ED |

Simple non-displaced tibial shaft fractures with no concerns for Compartment Syndrome | Within 1-2 days after discussion with on-call orthopaedic team | Fracture clinic or private rooms ** unlikely to be managed by GP ** |

Potential Complications

- Three of the four compartments of the lower leg, namely the anterior, posterior and deep posterior compartments, border the tibia.

- The vessels and nerves within these compartments can become significantly compromised due to swelling within these compartments as a result of tibial injury leading to compartment syndrome.

- Fractures of the middle third of the tibial shaft may compromise blood supply of the nutrient artery originating from the posterior tibial artery.

- Non-union.

Patient Advice

- Explain signs and symptoms of compartment syndrome.

- Pain from the fracture and restriction of movement is usual for 2-3 weeks and will require regular, then analgesia as required.

- Reinforce importance of strict elevation and non-weight bearing

- ECI patient factsheets

Patella Fractures

Summary

The patella is triangular shaped sesamoid bone with the apex directly distally. The subcutaneous location of the patella makes it exposed but injury is rare (.1,2 Fractures, if they do occur, are often as a result of a compressive (direct) force or tensile (indirect) force.

The patella is formed from the fusing of ossific nuclei. During this process, ossification of a second cartilaginous layer can result in the formation of a bipartite patella occurring in 0.2–6% of patients.3 Bipartite patella can be differentiated from acute patella fractures by their radiographic appearance: smooth, well-corticated borders with minimal separation.

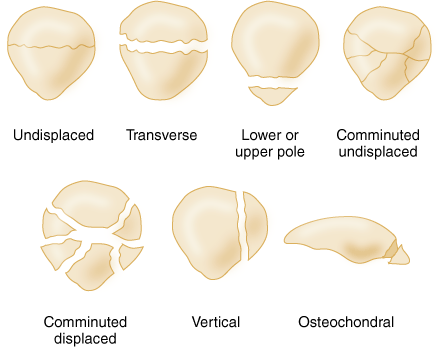

Classification

Various fracture patterns can result in stellate, transverse, vertical, marginal or osteochondral depending on the mechanism of injury. The most common patella fracture type is stellate, where a direct compressive force results in a comminuted pattern. Similarly common are transverse patella fractures, typically sustained during hyperflexion of the knee (tensile force) with eccentric contraction of the quadriceps. Patella fractures can be further classified as displaced (step-off >2mm and fracture gap >3mm) or undisplaced.3

Epidemiology

Patellar fractures account for about 1% of all fractures. They are most common in people who are 20-50 years old. Men are twice as likely as women to fracture the patella.3

Presentation

A patella fracture is suspected on the basis of a history of direct or indirect trauma to the knee and the presence of suggestive clinical findings, including acute knee swelling and focal patellar tenderness.

Imaging

X-Ray: anteroposterior, lateral, and sunrise views (although a “standard” sunrise view may not be obtainable if there is severe pain or a large effusion).3

ED Management Options

Undisplaced, closed patella fractures with intact extensor mechanism may be managed in ED with a POP backslab or removable splint.

The following need referral to orthopaedics in ED:

- Fractures with greater than 2mm of articular step-off

- Fractures with greater than 3mm of fragment separation

- Comminuted fractures, with or without displacement of the articular surface

- Disruption of the extensor mechanism

- Any open fracture or persistent neurovascular deficit requires immediate surgical referral

- Avulsion fractures involving the superior or inferior pole of the patella are essentially quadriceps (superior pole) and patellar tendon (inferior pole) injuries requiring surgical management.

Referral and Follow Up Requirements

Fracture Type | Management | Follow-up |

|---|---|---|

Undisplaced close patella fractures with intact extensor mechanism |

|

|

Displaced open/closed patella fracture, or avulsed patella fractures |

|

Potential Complications

Undisplaced patella fractures, non-operative intervention:

- Decreased knee range of motion (generally loss of terminal extension), weakness due to prolonged immobilization, nonunion, and patellofemoral joint pain.

- Increased risk of the development of osteoarthritis of the patellofemoral joint.

- Loss of terminal extension or persistent extension lag does occur, but it usually does not compromise function or the ability to return to sport. Nonunion is rare.

- Degenerative arthritis often develops after severely comminuted fractures.

- Patellofemoral pain, which is treated in standard fashion: icing, stretching of the hamstrings and iliotibial band, and strengthening of the quadriceps and gluteal muscles as indicated by examination.3,4

Displaced or open patella fractures, operative intervention:

- Infection, failure of hardware (e.g. wires breaking), decreased range of motion, nonunion, and osteonecrosis.3,4

Patient Advice

- Pain from the fracture and restriction of movement is usual for 2-3 weeks and will require regular, then prn analgesia.

- Refer to physio for advice and starting of mobilisation.

- Monitor for compartment syndrome.

- ECI patient factsheets

Further References and Resources

- Bhandari, M., ed. Evidence-based orthopedics. 1st ed. 2012, BMJ Books: London, UK.

- Blount, J. (2014) Patella fracture, cited in Uptodate March 2015

- Melvin, J. and Mehta, S., Patellar fractures in adults. Journal of American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 2011. 19(4): p. 198-207.

- Harris, R., Fracture of the patella, in Rockwood and Green's Fractures in Adults, Bucholz, R. and Heckman, J., Editors. 2002, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia.

Fibula Head

Summary

Fractures of the proximal fibula significance lies more with this fracture's association with injuries to the ligamentous and neurovascular structures than with the boney injury. It has a close association with ligamentous and neurovascular structures.

Classification

Classification is based on general fracture description and location.

Epidemiology

Can occur from direct trauma, ankle injuries from several mechanisms and as part of major trauma to the knee.

Presentation

A detailed history of the mechanism will help identify additional injuries to assess for.

A thorough knee examination should be performed, including the knee, tibia/fibula and ankle joint. Ensure to not the neurovascular status of the lower limb affected.

Examination will reveal tenderness over the proximal fibula. Look for additional injuries of the surrounding structures on examination, including knee effusion and ankle instability. There may be not obvious deformity of the leg if the tibia is intact.

The Maisonneuve fracture is a spiral fracture of the proximal third of the fibula associated with distruption of the distal tibiofibular syndesmosis +/- interosseous membrane, which results in an unstable ankle joint.

Imaging

X-rays include AP, lateral and oblique views of the knee and AP, lateral and mortise views of the ankle. AP and lateral views of the tibia and fibula shaft are also needed to assess the entire length of the leg.

MRI is appropriate if knee instability is detected or suspected.

Other imaging is directed by associated findings.

ED Management Options

Most injuries are treated symptomatically in a hinged knee brace and appropriate pain control. Early knee motion should be encouraged. Associated injuries are managed as found.

The proximal fibula fracture in a Maisonneuve injury does not require stabilisation. However, the intraossesous and/or syndesmotic injury may require fixation near the ankle if the distal tibiofilular joint is unstable. Closed reduction and casting is an additional treatment option.

Open reduction and internal fixation may be indicated acutely for boney avulsions of the LCL. Repair of associated posterolateral corner injuries to the knee can be stabilized at the same time.

Referral and Follow Up Requirements

Isolated injuries can be managed with hinged knee brace and follow up with orthopaedic clinic and physio. Where there is associated knee, ankle or any neurovascular injury consult orthopaedics at time of presentation.

Potential Complications

- Peroneal nerve injury - often the result of direct contusion and has a variable prognosis.

- Vascular injury - popliteal artery, from occult knee dislocation.

- Nonunion/malunion - may lead to varus knee instability if the LCL insertion is involved.

- Compartment syndrome – in high energy injuries.

Patient Advice

- Pain from the fracture and restriction of movement is usual for 2-3 weeks and will require regular, then analgesia as required.

- Refer to physio for advice and starting of mobilisation.

- Monitor for compartment syndrome.

- ECI patient factsheets

Further References and Resources

- Norvell J et al. (2015) Tibia and Fibula Fracture Treatment and Management, Medscape.

Tibial Plateau

Summary

A tibial plateau fracture occurs in the proximal part of the tibia involving the joint affecting the knee joint, stability, alignment and motion. The plateau is a critical weight-bearing area consisting of the medial and lateral condyles and the intercondylar ridge between. A typical tibial plateau fracture involves either cortical interruption, depression or displacement of the articular surfaces of the proximal tibia without and often without significant injury to the capsule or ligaments of the knee although this should always be considered.

Classification

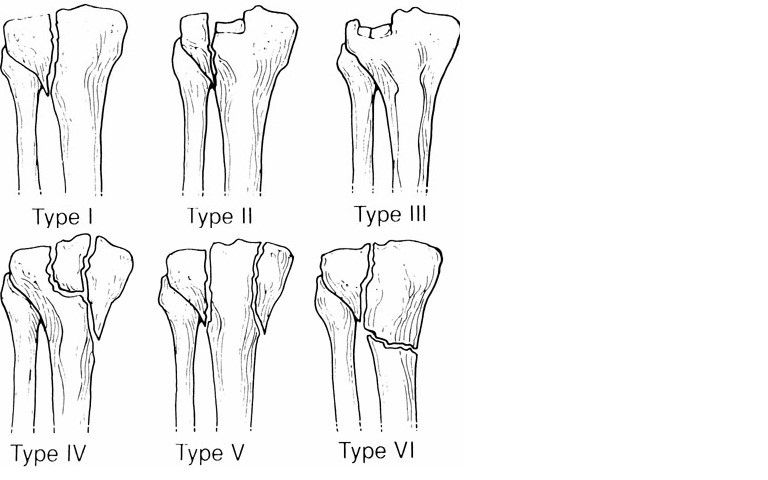

Schatzker classification for tibial plateau fracture:

Type | Description | Frequency | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

I | Lateral tibial plateau fracture without depression | ~6% | |

II | Lateral tibial plateau fracture with depression | 25% | Associated with distraction injuries to medial collateral and ACL |

III | Focal depression of articular surface | 36% | May result in joint instability if central tibial plateau involved |

IV | Medial tibial plateau fracture with/without depression | 10% | High risk of damage to popliteal artery and peroneal nerve. Associated with distraction injuries to lateral collateral and PCL |

V | Bicondylar tibial plateau fracture | 3% | |

VI | Tibial plateau fracture with dissociation of metaphysis from the diaphysis | 20% |

Epidemiology

Tibial plateau fractures constitute 1% of all fractures. Fractures of the tibial plateau are caused by a varus (inwardly angulating) or valgus (outwardly angulating) force combined with axial loading or weight bearing on knee. Tibial plateau fractures in the young (30-40 years) are typically due to high energy mechanisms such as MVA. In the older female population (60-70 years) they are usually due to low–energy mechanisms in osteoporotic bones. The classically described situation is from a car striking a pedestrians fixed knee (‘bumper fracture’).

Presentation

Tibial plateau fractures typically presents with swelling and inability to bear weight. There may be deformity. The swelling is generally a haemarthosis. With displaced fractures there can neurovascular compromise and this may be part of the presentation. Compartment syndrome can occur with more extensive injury and should always be considered. Approximately 50% of the knees with closed tibial plateau fractures have injuries of the menisci and cruciate ligaments that usually require surgical repair.

Imaging

Plain films: AP and lateral will for the most part give the diagnosis. CT scanning may be of value to for operative planning or decision making. Oblique projections should be added if a nondisplaced tibial plateau fracture is suspected but not seen on the standard projections.

The presence of a lipohemarthrosis or malalignment of the tibial plateaus are pointers to fractures, where there is strong clinical decision of a fracture a CT scan may be of benefit.

MRI is required to identify or confirm cartilaginous or soft tissue injuries.

CT angiography should be considered if reduced/absent distal pulses, particularly in a Type IV injury where there is an increased incidence of associated vascular injury.

ED Management Options

Early immobilisation of the knee, identification of any neurovascular injury and identification of compartment syndrome complement the usual emergency management such as adequate analgesia and whole patient management. The patient should be non weight bearing.

Referral and Follow Up Requirements

Referral should be review in the ED where possible. Non displaced fractures with no neurovascular involvement and no compartment syndrome can be immobilised, non weight bearing and reviewed in fracture clinic within the week. All other fractures should have orthopaedic referral.

Potential Complications

- Neurovascular

- Compartment syndrome

- Cartilaginous injury

- Ligamentous injury

- Long term arthritis.

Patient Advice

As per POP care and crutches if discharged with these.

- Pain from the fracture and restriction of movement is usual for 2-3 weeks and will require regular, then analgesia as required.

- Monitor for compartment syndrome.

- Refer to physio for advice and starting of mobilisation.

- ECI patient factsheets

Further References and Resources

- Vidyathara, S et al. (2015) Tibial plateau Fractures Treatment and Management, Medscape.

- Orthobullets - tibial plateau fractures

- Patient (UK) - knee fractures and dislocations

- Markhardt K, Gross J, Monu Johnny. Schatzker Classification of Tibial Plateua Fracture: Use of CT and MR Imaging Improves Assessment. RadioGraphics 2009; 29:585-597.