End of Life Care in the Emergency Department

Introduction

Caring for patients in the emergency department who are reaching the end of life is complex and at times difficult, but also a very rewarding part of your clinical practice when done well. Decisions and conversations with relatives and carers of patients about resuscitation status, advance care plans and patient wishes can be difficult and should be handled in a sensitive, compassionate and professional manner. Prescribing for a patient who may be imminently dying and organising death certification may be an area you are uncomfortable with.

For these reasons we have pooled a number of resources with quick links to help you navigate the relevant areas.

Curative care or comfort care

To assist in the conversations you may have we provide a link below. We know that for the most part the decision is clinical but a delicately handled conversation can relieve anxiety and avoid misunderstandings or unrealistic expectations further along the clinical path. It is imperative to make a clear decision and communicate it to all treating clinicians as well as document well and clearly in the notes. Limitations must be clearly spelled out and be consistent with information you have communicated.

Using Resuscitation Plans in End of Life Decisions

A Resuscitation Plan is a medically authorised order to use or withhold resuscitation measures which documents other aspects of treatment relevant at end of life.

The Policy Directive Using Resuscitation Plans in End of Life Decisions published by the Office of the NSW Chief Health Officer describes the standards and principles relating to appropriate use of Resuscitation Plans by NSW Public Health Organisations for patients aged 29 days and older.

Under the Policy Directive, all Public Health Organisations must:

- Adopt the state Resuscitation Plans (adult and paediatric) – see Forms below for examples. These should replace similar existing LHD forms (e.g. No CPR Orders, Not for Resuscitation Orders)

- Incorporate evaluation of whether Resuscitation Plans were completed into death audit protocols.

Medications

As a person reaching the end of life begins to deteriorate their regular medications may not need to be administered. The important medications to remember charting before the patient leaves the emergency department are for pain, anxiety/sedation, increased secretions and nausea/vomiting. Consider withdrawal which may occur with narcotics, benzodiazepines, SSRI and similar medications and even b-blockers, the withdrawal of these and some other medications may lead to unnecessary distress.

Last Days of Life Toolkit

To improve and support the care of dying patients, the Clinical Excellence Commission has developed a last days of life toolkit.

The toolkit provides tools and resources to ensure all dying patients are recognised early, receive optimal symptom control, have social, spiritual and cultural needs addressed, both patient and families/carers are involved in decision-making, and bereavement support occurs. It has been specifically developed for use by generalist clinicians and is not intended to replace either local Specialist Palliative Care guidelines or advice given by Specialist Palliative Care clinicians.

Certification of death

This part gives information on verifying and certifying death, cases to report to the coroner and cremation.

Direction of Care Conversation

Initially it is important to establish trust. For example, after introductions offer your apologies for the precipitant nature of this conversation but state clearly that you want what is best for the patient and also to follow the patient’s wishes. State you need to get a quick idea of what the patient wants or would have wanted in this situation (if the patient lacks capacity1).

Early questions to ask

- Does the patient have an Advance Care Directive?

- Is the Advance Care Directive up to date?

If the answer is No or unsure then 2 further questions to be asked

- Does the patient have the capacity to make an informed decision?

- If not are there family members/Next of Kin present or an identified Person Responsible?

Things to think about before you start the discussion

- It is important that you establish the ‘Goals of Care’ early on in the conversation.

- The key words are ‘Curative Care’ or ‘Comfort Care’.

- Ask the question ‘If treatment could prolong your life, what level of quality of life would be acceptable to you’.

- Steer away from the concept ‘All or nothing’ and emphasise that although palliation has been chosen, everything will be done to ensure patient comfort.

- Patient Factors which can assist in goal direction:

- Age of patient and where the patient resides?

- The general state of the patient-skin integrity, nutritional state, continence

- Quality of life-use the Karnofsky2 performance status scale or simply ‘How much time do you spend in bed’

- Cognitive state

Always remember to involve the Social Worker and Spiritual/Pastoral care if required.

Your patient is deteriorating as the discussion is being held/fine tuned?

- Initiate stabilization measures

- Airway/Breathing - Oxygen, Non-Invasive Ventilation can buy time

- Circulation/Hypotensive - Fluids, remember that Adrenaline can be given peripherally short-term while considering the level of patient treatment

- Pain - Give analgesia

The decision cannot be reached or the patient’s requests differ from your management plan?

- Involve your ICU and consider a trial of critical care over an agreed timeframe.

Footnotes

1 Hierarchy of Person Responsible Guardianship Act

2The Australia-modified Karnofsky Performance Status (AKPS) scale: a revised scale for contemporary palliative care clinical practice Abernethy A P, Shelby-James T, Fazekas B S, Woods D and Currow D C BMC Palliative Care 2005, 4:7

Further References and Resources

- Emergency Medicine Cases - Episode 70 End of Life Care in Emergency Medicine

The Hospital Resuscitation Orders Form

In explaining the form to the patient it is important that the patient and/or family understand the language that you use.

Explanation of terms:

- Palliative care: treatment that is not aimed at a cure but at caring for the patient by keeping him/her as physically comfortable and pain-free as possible, while also attending to his/her emotional, mental, social and spiritual needs.

- Cardiopulmonary resuscitation: emergency measures to keep the heart pumping (by massaging chest or using electrical stimulation) and artificial ventilation (mouth-to-mouth or ventilator) when breathing and heart beat have stopped.

- Assisted ventilation: use of a machine, such as a ventilator, to help the patient breathe when he/she is unable to breathe unaided.

Certification of the Deceased patient in the Emergency Department

Action 1: Verify Death

This is done by demonstrating the following:

- No palpable carotid pulse and

- No heart sounds heard for 2 minutes and

- No breath sounds heard for 2 minutes and

- Fixed and dilated pupils and no response to centralised stimulus and

- No motor (withdrawal) response or facial grimace in response to painful stimulus

Optional:

- ECG strip shows no rhythm

When the patient has been treated in the emergency department (ED) the death certificate can be written by the patient’s usual GP or hospital team or by the ED doctor.

A patient who has not been treated by the ED can be brought to the department for declaration of death. This usually occurs when a government contractor brings the body from place of death to the emergency department for declaration, en route to the morgue. Typically, the medical officer signs paperwork the government contractor has or can fill a Life Extinct form, an example of which is found in the Forms section. Gathering information about the cause of death is not the responsibility of the ED

Action 2: Certify Death (see example in forms)

The medical certificate of cause of death is divided into 3 sections:

- Part I - Diseases or conditions directly leading to death and antecedent causes

- Part II - Other significant conditions

- A column to record the approximate interval between onset and death

- You complete the medical certificate of cause of death if a diagnosis for cause of death can be made.

- If you are unable to ascertain the cause of death or have any concerns the matter should be referred to the Coroner. Outside of working hours contact local police.

- Use black ink to complete the form.

- Avoid using the mode of dying, such as cardiac arrest or brain death.

Action 3: Coroners Case/Form A (see example on the End of Life examples of forms page)

There are some deaths which must be reported to the Coroner and a certificate as to the cause of death should not be issued:

- the person died a violent or unnatural death

- the person died a sudden death the cause of which is unknown

- the person died under suspicious or unusual circumstances

- the person died in circumstances where the person had not been attended by a medical practitioner during the period of six months immediately before the person’s death

- the person died in circumstances where the person’s death was not the reasonably expected outcome of a health related procedure carried out in relation to the person

- the person died while in or temporarily absent from a declared mental health facility within the meaning of the Mental Health Act 2007 and while the person was a resident at the facility for the purpose of receiving care, treatment or assistance

OR

- If the death is a death under s24 Coroners Act.

For a more detailed explanation please refer to the NSW Health Coroners Cases and Coroners Act 2009.

An example of 'Form A' can be found on the End of Life examples of forms page.

Action 4: Cremation

The deceased may require a cremation certificate to be completed, The Attending Practitioner's Cremation Certificate is available on the End of Life examples of forms page.

A medical officer can complete the form if they are able to certify the cause of death and the death is not examinable under the Coroners Act 1980. The practitioner must have seen and identified the body after death.

Remember to identify if the deceased has a pacemaker/defibrillator and ensure that it has been switched off.

Action 5: Inform

- Relatives, VMO, General practitioner.

- Do discharge summary for the patients health care record.

Organ Donation

Early referral from the ED increases likelihood of successful organ donation, however it has been shown that the same person who informs relatives of bad news is not the best placed person to discuss organ donation with them.

The job of the ED physician is to identify patients who are potential organ donors. This process should not influence decisions regarding resuscitation or the ongoing treatment of the patient, and it is not the role of the ED doctor to discuss organ donation.

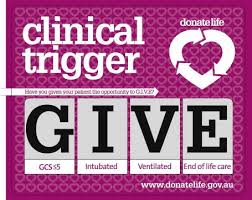

Trigger: G=GCS ≤ 5, I=Intubated, V=Ventilated, E=End of life discussions.

The Clinical Trigger is met in patients from ED or ICU with an irrecoverable brain injury where GCS ≤ 5, Intubated and ventilated with whom end of life decisions have been initiated.

Large Hospitals in NSW have an on-call clinician for organ donation. You should call them and discuss and patient who meets criteria for discussion.

Further References and Resources

Breaking Bad News: Death in ED

Death in the ED is often unexpected, and breaking bad news to loved ones after the death of a patient is stressful and emotionally challenging for even the most experienced ED physician.

Whilst it is a difficult scenario for us, it is much more so for the family/ next of kin. Showing empathy and compassion whilst being careful to communicate effectively will avoid misunderstandings at this stressful time.

Before you begin, think about the following points.

Prepare

- Team – A doctor and nurse who treated the patient, consider social worker and spiritual care.

- Space – Ensure the space is suitable- large enough for the family, quiet, private and confidential

- Privacy – As above, ensure you will not be disturbed. Let someone know where you will be and that you are not to be disturbed. Turn off your phone / pager.

The Conversation

- Use appropriate body language – be compassionate and sincere

- Introduce yourself and other team members

- Ask families their names and relationship to the patient

- Give a warning shot. Often our body language is enough that relatives recognise bad news is on its way, but key phrases such as “I’m afraid I have bad news” are useful.

- Use clear language with no jargon for example “I am very sorry, but your husband suffered a heart attack and has died”

- Provide assurance and as much or as little medical information as you think necessary.

- Allow time for reflection and for silence.

- Answer any questions the family may have. Be honest, the answer may be “I don’t know”.

A useful mnemonic, VALUE has been described:

- Value and appreciate what family members say.

- Acknowledge the family’s emotions.

- Listen.

- Ask questions which would help the caregiver understand who the patient is.

- Elicit questions from the family members.

Finishing

- Ensure the family has follow up for any questions they may have (go back and see them in 15 minutes)

- Offer access to spiritual or religious services

- Ensure the family will know about what happens next (eg where the body will go, coroners case).

- Document the discussion in your notes

- Team debrief

Further References and Resources

End of Life Resources

Patient Factsheets

Further learning opportunities in Australia:

- The Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital in Queensland offers their emergency trainees a 6 month rotation with the palliative care service and completion of a Diploma in Palliative Medicine. Dr William Lukin. Email: bill_lukin@health.qld.gov.au

Relevant Australasian papers:

- Todd, K. H. (2012), Practically speaking: Emergency medicine and the palliative care movement. Emergency Medicine Australasia, 24: 4–6.

- Lukin, W., Douglas, C. and O'Connor, A. (2012), Palliative care in the emergency department: An oxymoron or just good medicine?. Emergency Medicine Australasia, 24: 102–104.

- Clayton, J.M. et al. (2007), Clinical practice guidelines for communicating prognosis and end-of-life issues with adults in the advanced stages of a life-limiting illness, and their caregivers. Med J Aust, 186 (12): 77.

- Forero, R. et al. (2012) A Literature Review on Care at the End-of-Life in the Emergency Department. Emergency Medicine International, vol. 2012, Article ID 486516, 11 pages. doi:10.1155/2012/486516

International papers and resources:

- Emergency Medicine Cases - Episode 70 End of Life Care in Emergency Medicine

- First10EM - Breaking bad news: Notifying family members of a death in the emergency department

Presentations

- Death, Dying and Other Difficult Conversations - Dr Sanj Fernando and Dr Allan Giles at the ECI FACEM Wisdom Fast Tracked 4 December 2015

- Non-beneficial treatments at the end of life - Magnolia Cardona-Morrell, Senior Research Fellow, The Simpson Centre for Health Services Research, SWS Clinical School at the ECI ED Leadership Forum 5 August 2016

- Panel Discussion: The elderly patient - challenging decisions in emergency care at the ECI ED Leadership Forum 5 August 2016

Useful Australian Websites:

- Start2Talk - an advance care planning (ACP) national website developed by Alzheimers Australia.

- DonateLife - information for health professionals working in the donation sector

- CareSearch palliative care knowledge network - a suite of palliative care information and resources designed to support health professionals involved in providing palliative care

- palliAGED - an online evidence-based resource about palliative care in aged care for use by health professionals and the aged care workforce

- Using Resuscitation Plans in End of Life Decisions, PD2014_030, NSW Health, 8 September 2014

- Coroners Cases and The Coroners Act 2009, PD2004_054, NSW Health, 1 September 2010

- Management of the Potential Organ and Tissue Donor following Neurological Determination of Death, GL2023_013, NSW Health, 5 April 2023

- Advance Planning for Quality Care at End of Life - Action Plan 2013-2018, NSW Health, 11 July 2013

Death Certification:

- Information Paper: Cause of Death Certification Australia, Australian Bureau of Statics, 2008

- State Coroners Court of New South Wales

Death Audits

- ECI ED Quality Framework Death Audit Tools

Cultural Awareness and End of Life Care

Given the multicultural nature of Australian society, it is important for ED staff to be aware of attitudes towards death and dying in different cultures. We provide some resources which may assist you when approaching patients and their families from different backgrounds with regards to end of life discussions.

Resources

Palliative Care Australia – Multicultural Palliative Care Guidelines

These provide an overview of different language and cultural groups living in Australia. Please note that these are a guideline only and that every individual is different.

Centre for Cultural Diversity in Aging – Cultural awareness

Diversicare - Cultural Profiles

ACEM - Palliative Care Resources

These resources include links relating to studies in palliative care in different cultural groups.