Published: June 2021

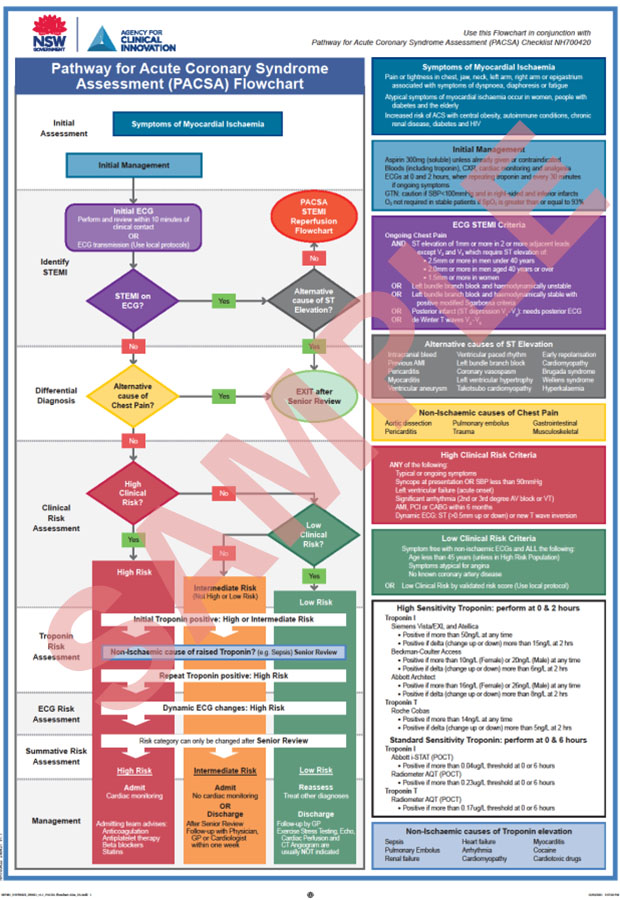

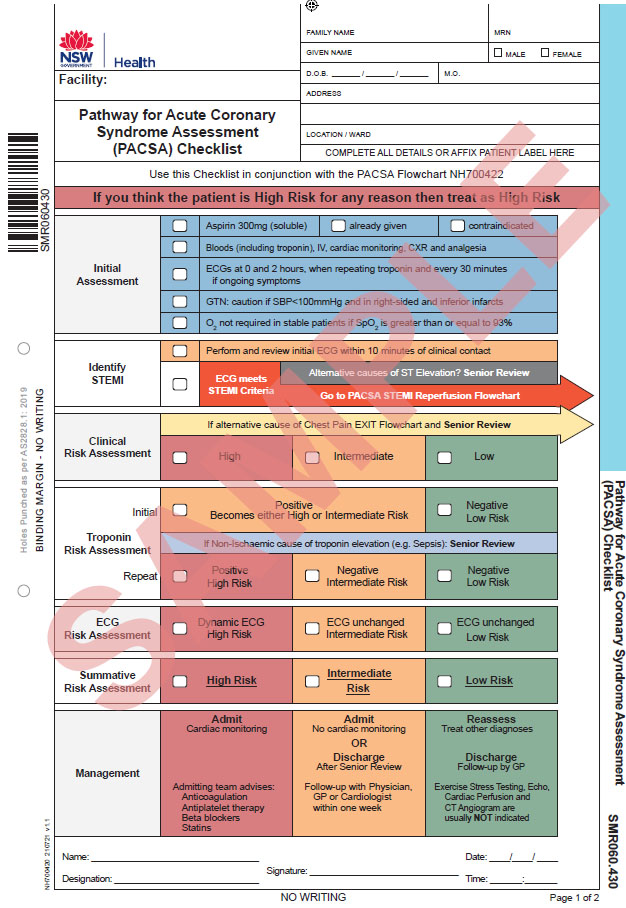

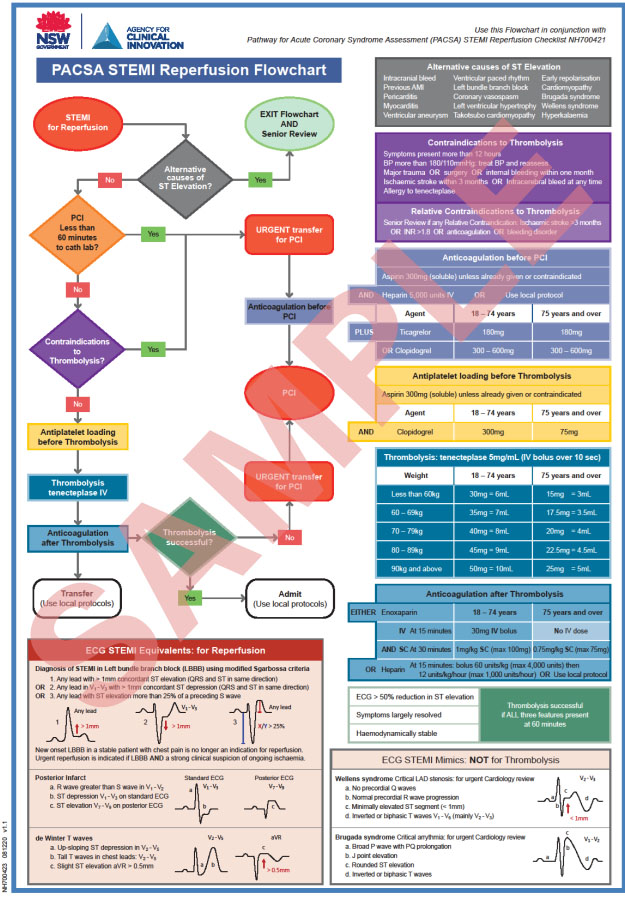

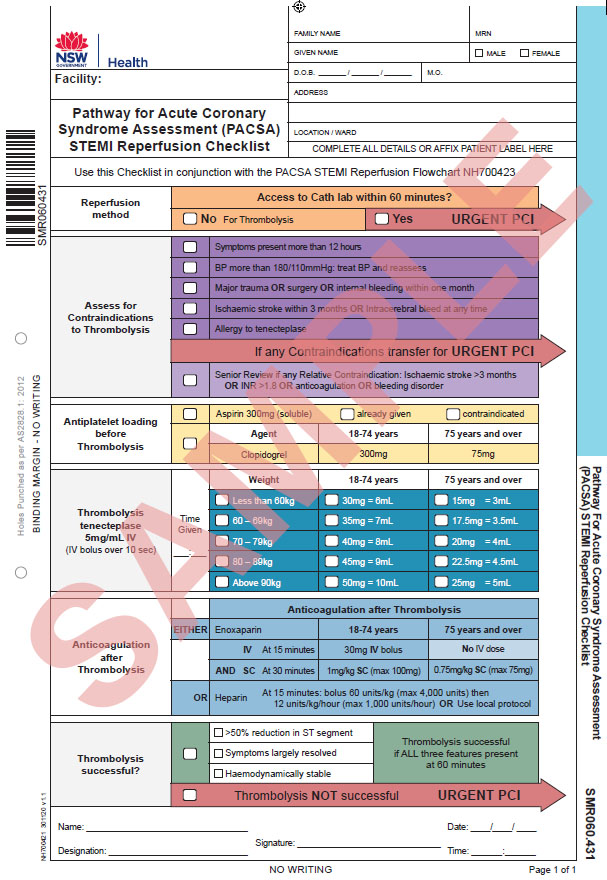

The Pathway for Acute Coronary Syndrome Assessment (PACSA) is a set of documents that outline how to assess and manage patients with suspected acute coronary syndrome (ACS).

PACSA has been designed to standardise practice across all health services operating in NSW, including in rural, regional and metropolitan areas.

It is not designed to be a comprehensive review of the assessment and management of ischaemic heart disease and should be used in conjunction with other clinical resources.

What’s new in this update

Updates from the previous version GL2019_014 include:

- minor changes to wording around clinical risk assessment classification

- formatting changes to the flowcharts and checklists

- additional inclusions at initial assessment regarding glyceryl trinitrate (GTN) and oxygen

- removal of guidance regarding Prasugrel as anticoagulation before percutaneous coronary intervention

- adjustment of dosages for Clopidogrel as anticoagulation before percutaneous coronary intervention.

PACSA resources

PACSA consists of four documents: 2 flow charts and 2 checklists.

| Title | Product code | Click to download sample |

|---|---|---|

| PACSA flowchart | NH700422 |  |

| PACSA checklist | NH700420 |  |

| PACSA STEMI reperfusion flowchart | NH700423 |  |

| PACSA STEMI reperfusion checklist | NH700421 |  |

The PACSA flowchart and the PACSA STEMI reperfusion flowchart outline each step of patient management with corresponding colour-coded details on the right hand side. Each flow chart has a corresponding checklist.

The PACSA flowchart, the PACSA checklist, the PACSA STEMI reperfusion flowchart and the PACSA STEMI reperfusion checklist are available from the NSW Health State Forms catalogue. The product numbers are listed above for each flow chart/checklist. NSW Health staff can order and print forms via Finsbury Green (login required) or use your local print ordering process.

More information for NSW Health staff is available on the HealthShare intranet.

How to use PACSA

The first step in PACSA is to identify patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) who require reperfusion.

If no STEMI is identified, perform a sequential risk stratification using:

- clinical features

- troponin testing

- electrocardiogram (ECG) findings.

The integration of these results provides a summative risk assessment that directs clinical management of the patient.

Clinical risk assessment

An important principle of PACSA is that the clinical risk of a patient should be assessed before undertaking troponin testing.

The first step in PACSA is to assess if the patient is high clinical risk, using the definition of ‘high risk’ from the National Heart Foundation of Australia (NHFA) and the Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand (CSANZ).1

If a patient does not meet high risk criteria, they are assessed to see if they are low clinical risk. There are a number of low risk algorithms available.

If the patient is not high risk and is not low risk, they should be classified as intermediate risk.

In high-risk populations, ACS can present at a younger age.2,3 These include people with:

- diabetes

- renal disease

- autoimmune disorders

- HIV

- strong family history of cardiovascular disease.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ethnicity is not an independent risk factor but is associated with multiple cardiac risk factors.4

Psychiatric illness is not an independent risk factor for ACS but is also associated with multiple risk factors for ischaemic heart disease and poorer outcomes.5

Atypical symptoms of ACS occur more commonly in women,6 the elderly and people with diabetes. Atypical symptoms include unusual patterns of pain, fatigue and shortness of breath.7

Troponin risk assessment

The predictive value of clinical risk scores is increased when used in conjunction with troponin tests and serial ECGs.8,9,10,11,12

An initial elevated troponin result does not necessarily indicate acute myocardial infarction (AMI) but it does indicate that the patient is not low-risk. This group has higher all-cause mortality as well as greater risk of ACS.

A repeat troponin test is recommended if a patient has had symptoms within the previous six hours or if the patient is high- or intermediate-risk.

For low-risk patients, a single troponin test may be sufficient if it is performed more than six hours after symptoms cease.

Troponin assays are regarded as positive above a defined threshold (refer to the PACSA Flow Chart). High-sensitivity (HS) troponin assays also allow for a positive result via a change (delta) either up or down, between repeated troponin tests. This is known as a positive delta troponin13and is associated with ischaemic causes of chest pain and high risk. A troponin assay is regarded as positive by delta even if both troponin results are in the normal range.

All laboratory-based troponin tests in NSW use HS assays. These should be repeated after two hours to obtain a delta. Absolute delta values are more reliable than relative (or percentage) delta values.14

All point of care (POC) troponin tests in NSW use standard-sensitivity assays. POC troponin test results are regarded as positive above a defined threshold (refer to the PACSA Flow Chart). They are not currently reproducible enough to allow the use of delta troponin. A POC troponin test can be repeated at any time and is useful if positive. A patient should not be discharged unless they have had a negative six-hour POC troponin test result.

HS and POC (standard sensitivity) troponin results are not interchangeable.

The threshold and delta levels for all HS troponins used in NSW are listed in the PACSA flowchart.

ECG risk assessment

The initial ECG is performed to identify if the patient has a STEMI. The criteria for STEMI and STEMI equivalents are shown in the PACSA STEMI reperfusion flowchart. STEMI equivalents include left bundle branch block (LBBB) in an unstable patient, LBBB with modified Sgarbossa criteria, posterior infarction and de Winter T waves.

STEMI mimics include Wellens and Brugada syndromes. These are both high-risk conditions and require cardiology referral. However, they are not indications for thrombolysis.15

A minimum of two ECGs are required: one on arrival and another at two hours. ECGs should also be performed when repeating troponin tests and every 30 minutes if there are ongoing symptoms. Dynamic ECG changes are a marker of high risk.

Summative risk assessment

The integration of clinical risk, troponin results and serial ECGs determines a summative risk that directs further management of the patient.

Summative risk assessment provides an opportunity for senior decision-makers to modify the risk category determined by PACSA.

Clinical judgement continues to play an important role, as negative troponin results do not exclude coronary artery disease, as a cause of symptoms and positive troponin results are not always due to cardiac ischemia.

Shared decision-making and establishing goals of treatment with each patient is the expected standard of care.

STEMI transfer

Each local health district (LHD) should facilitate transfer of patients with STEMI in line with the State Cardiac Reperfusion Strategy (SCRS).16

Background

PACSA was developed to replace the 2011 NSW Health Policy Directive PD2011_037 Chest Pain Evaluation (NSW Chest Pain Pathway).

The Clinical Excellence Commission reviews adverse events associated with acute coronary syndrome.17 Between July 2015 and June 2017 there were 23 serious incidents, including 13 rated severity assessment code 1 (SAC 1). These were characterised into themes to inform development of a new pathway. More than 300 papers relating to cardiac biomarkers and their use in rapid assessment pathways were examined. Australasian and international chest pain pathways were reviewed.18,19

NSW Pathology was engaged to derive the PACSA troponin values. There were three rounds of consultation with clinicians across NSW. PACSA was tested in rural, regional and metropolitan facilities.

The evidence regarding assessment and management of suspected ACS is rapidly evolving. PACSA will require revision and updating as new information becomes available.

References

- Chew, DP, Scott, IA, Cullen L et al. National Heart Foundation of Australia & Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand. Australian clinical guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes 2016. Heart, Lung, Circulation. 2016;25(9): 895-95.

- Vachiat A1, McCutcheon K1, Tsabedze N1 et al. HIV and ischemic heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 Jan 3;69(1):73-8.

- Abdulrahman A, Feinstein MJ. Coronary artery disease in HIV. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Jan 18.

- Heart Foundation. Indigenous lifestyle is major factor for increased cardiac risk factors. Australia: Heart Foundation; 2023 [cited June 2021].

- Lambert TJR, Newcomer JW. Are the cardio-metabolic complications of schizophrenia still neglected? Barriers to care. MJA. 2009;190(4):S39-S42.

- Gulati M. Improving the cardiovascular health of women in the nation. Circulation. 2017;135: 495-498.

- Cedar Sinai. Information for consumers on heart attack. USA: Cedar Senai; 2023 [cited June 2021].

- Wildi K, Cullen L, Twerenbold R et al. Direct comparison of two rule-out strategies for acute myocardial infarction: 2-h Accelerated Diagnostic Protocol vs 2-h algorithm. Clin Chem. 2017;63(7):1227–1236.

- Mahler S, Riley RF, Hiestand BC et al. The HEART Pathway Randomized Trial: Identifying emergency department patients with acute chest pain for early discharge. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2015;8(2):195-203.

- Veld MAH, Cullen L, Mahler SA et al. The fast and the furious: Low-risk Chest Pain and the Rapid Rule-out Protocol. West J Emerg Med. 2017;18(3):474–478.

- Roche T, Jennings N, Clifford S et al. Diagnostic accuracy of risk stratification tools for patients with chest pain in the rural emergency department: a systematic review. Emerg Med Australas. 2016;28(5);511-524.

- Reichlin T, Twerenbold R, Wildi K et al. Prospective validation of a 1-hour algorithm to rule-out and rule-in acute myocardial infarction using a high sensitivity cardiac troponin T assay. CMAJ. 2015;187(8).

- Cullen L, Greenslade JH, Hawkins T et al. Improved Assessment of Chest pain Trial (IMPACT): Assessing patients with possible acute coronary syndrome. MJA. 2017;207(5).

- Storrow AB, Nowak RM, Diercks DB et al. Absolute and relative changes (delta) in troponin I for early diagnosis of myocardial infarction: results of a prospective multicenter trial. Clin Biochem. 2015;48(4-5):260-267.

- Wall J, White LD, Lee A. Novel ECG changes in acute coronary syndromes. Would improvement in the recognition of ‘STEMI-equivalents’ affect time until reperfusion? Int Emerg Med. 2018:13(2):243-249.

- Agency for Clinical Innovation. State cardiac reperfusion strategy (SCRS). Cardiac Network. Sydney: ACI; 2020 [cited June 2021].

- Clinical Excellence Commission. Second review of acute coronary syndrome incidents. Sydney: CEC; 2013 [cited June 2021].

- Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. . Sydney: ACSQHC; 2015 [cited June 2021].

- Roffi M, Patrono C, Collet JP et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: Task force for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2016;37(3):267-315.