Module 10 - Power wheelchairs

Aim

This module aims to provide information about power wheelchair (PWC) interventions and prescriptions to meet the needs of clients with a spinal cord injury, who require powered mobility for independence. It also aims introduce the components of a PWC system and provide an introductory description of the clinical considerations which underlie the use and configuration of these components.

Note: only the types of PWC for independent mobility commonly used by clients with a spinal cord injury will be discussed in this module.

Rationale

The PWC configuration influences the seating position of the client and interaction with the environment. A successful PWC prescription integrates the goals of optimal posture and pressure management as established in Module 7 and Module 8 , as well as functional capability and comfort.

Outcomes

At the end of this module, you should be able to:

- Recognise the different types of PWC

- Recognise indicators for PWC assessment

- List the components of a PWC

- List the common types of power seating functions and their applications

- Understand the key issues on prescribing or customising a PWC for clients with a spinal cord injury

- Recognise that the supplier is a resource for equipment assessment and trial processes

- Conduct a PWC trial with set criteria to make informative choice

- Have access to downloads and links to useful resources

In this module

- Prescription of a power wheelchair

- Types of powered mobility

- Keep the big picture in mind

- Components of a power wheelchair

- Be systematic: Identifying key issues for appropriate power wheelchair prescription

- Medical diagnosis

- Surgical history

- Upper limb pain

- Neck pain

- Pressure injuries

- Bladder management

- Weight gain or loss

- Psychosocial and carer issues

- Functional tasks

- Environmental context

- Transportation

- Existing seating and wheeled mobility limitations

- Work as a team

- Formulate

- Persevere!!

- Key concepts in this module

- Case study: Katherine

- Case study questions

- Case study answers

Prescription of a power wheelchair

As in manual wheelchair seating, power wheelchair seating has the following clinical objectives:

- To protect the tissue integrity of the user

- To allow optimal mobility of the user

- To create or to maintain normal anatomical alignment with particular attention to the spine1, and

- To provide a comfortable seating configuration.

While the four clinical objectives of seating generally support each other, there are occasions where improvements in one objective may adversely affect the outcomes in one or more of the other objectives. In discussion with the client and other relevant individuals, the clinician will also determine what goals the client has for daily living and community engagement.

When considering each of the four clinical objectives above it is prudent to consider seating goals as either essential or desirable. Essential goals relate to the clients daily needs and requirements, while desirable goals extend beyond that which is necessary. For example, the minimum essential goal for pressure care might be to allow for wheelchair seating for the duration of a necessary daily activity without skin marking, while the desirable goal might be to sit in the chair all day, or perform certain non-essential activities, without damage to the skin.

Once minimum essential goals are determined the clinician and client can discuss what the desired goals are, and determine what intervention/configuration is required to achieve this outcome, if it can be achieved.

A successful wheeled mobility prescription integrates the goals of postural alignment and pressure management as established in Module 7 and Module 8. Appropriate PWC and seating requirements are selected to achieve the best combination of client’s health status, functional independence and community participation, inaccordance with the seating goals of the client and relevant parties.

With the rapid rate of technological advancement in seating and wheeled mobility, a replacement PWC is unlikely to be exactly the same as the previous one. Minor changes can impact on the client’s posture, pressure management, functional abilities and their access to the environment. A thorough clinical assessment and up-to date technical support from the suppliers or specialists will be required to ensure that a replacement prescription meets the client’s needs.

For clients with a spinal cord injury who experience chronic upper limb pain and injury, assessment for PWC has been recommended in the ‘Preservation of upper limb function following spinal cord injury: a clinical practice guideline for health-care professionals’.2

A power wheelchair is clinically indicated for a range of clients. It is convenient to consider clients in three groups: new wheelchair users, existing PWC users needing replacement equipment, and clients whose seating and mobility needs have changed.

Indicators for PWC assessment and intervention:

- Client level of injury, balance or function which requires a PWC to meet seating goals

- Inability to independently perform an effective weight shift, requiring power seating functions for pressure management

- The presence of significant functional limitations, postural asymmetry and deformity which contraindicate manual wheelchair mobility

- A change in functional mobility status since the last prescription of equipment

- A change in the client’s ability to use existing PWC control devices

- Upper limb pain or deterioration relating to propulsion of a manual wheelchair

- Replacement of existing powered mobility equipment

- Powered wheelchair safety concerns of client or carers.

In the course of a clinical interaction, the therapist may be provided with information that highlights the need for a review of a client’s health, functional capability, equipment and/or environment. Such a review may lead to an assessment for a power wheelchair. PWC assessment and intervention may take different forms such as:

- An assessment of client function and capability in line with clinical objectives and client goals

- Adjustment of the current seating system or power base

- Upgrading or replacing of components of current power wheelchair,

- Trialling of equipment and qualitative/quantitative assessment of effectiveness, or

- Prescribing new PWC equipment and subsequent training for the client and/or carer(s).

In some instances there may be complicating factors, and local therapists may require support. In these cases, the client can be referred to a Spinal Seating Service.

Referrals to a Spinal Seating Service are indicated for clients with:

- Significant postural deformities

- An inability to maintain a good seating posture throughout the day

- Complex postural and functional needs where commercial products are not able to meet the desired outcome

- Custom-fabricated products that require replacement, such as: cushions, custom-made backrests, armrests and foot supports

- Unmanageable discomfort or skin marking

- Non-healing, sitting-acquired pressure injuries

- A history of recurrent pressure injuries

- Previous surgical interventions relating to pressure injuries

- Dependence on a respiratory ventilator, or

- Difficulty in resolving safety concerns with seating and mobility equipment.

References

- Hastings JD. Seating assessment and planning. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am.[Internet]. 2000 Feb;11(1):183-207, x. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10680165.

- “Recommendation 34: Encourage manual wheelchair users with chronic upper limb pain to seriously consider use of power wheelchair” Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine, 2005 Apr, published by Paralyzed Veterans of America, accessed 2008.

Types of powered mobility

Power mobility devices may be considered under the following classes:

- Scooters

- ‘Power add-on’ or ‘propulsion-assist’ units

- Folding PWCs

- Power base PWCs

Scooters are three or four wheeled mobility system steered with a tiller. These are rarely used by clients with SCI and typically have no scope for variation in components to address the four clinical objectives of seating. They are not covered in this module. For more information regarding the prescription of scooters as mobility devices please refer to the ‘Enable NSW prescription and provision guidelines for mobility scooters’.1

Power Add-on / Propulsion-Assist Units are detachable or semi-detachable units for adding power wheelchair to a manual wheelchair. As this class of powered wheelchair relies upon a manual wheelchair for seating it is covered in depth in Module 9.

Folding power wheelchairs, intended for transport when folded, have a folding frame and batteries that may be detached for transport. There are no power seating options, very limited seating adjustment, and there may be very limited programming capability of the wheelchair controller. Folding PWC are not covered in this module as this class of chair has largely been superseded. Examples of folding PWC include: 'Invacare 9000', 'Glide 4'.

Power wheelchairs (PWC) consist of a power drive base unit with a seating system mounted on the base. In general there is a wide range of options for customisation in seating and drive performance. The control device may be interfaced with other access devices such as computers and environmental control units. Simple power wheelchairs are also available with basic seating systems if sufficient for client needs.

References

- Enable NSW. Prescription and provision guidelines [Internet]. Health Support Services: Enable NSW; 2011 [cited Oct 2015]. Available from: https://www.enable.health.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/263094/Prescription-and-Provision-Guideline-Ambulant-Mobility.pdf

Keep the big picture in mind

The wheelchair should be appropriate for the client’s body ‘size’ and ‘shape’ to optimise pressure care, postural alignment, maximise an individual’s functional abilities and comfort. It should enable the client to function in their life roles and in their environment.

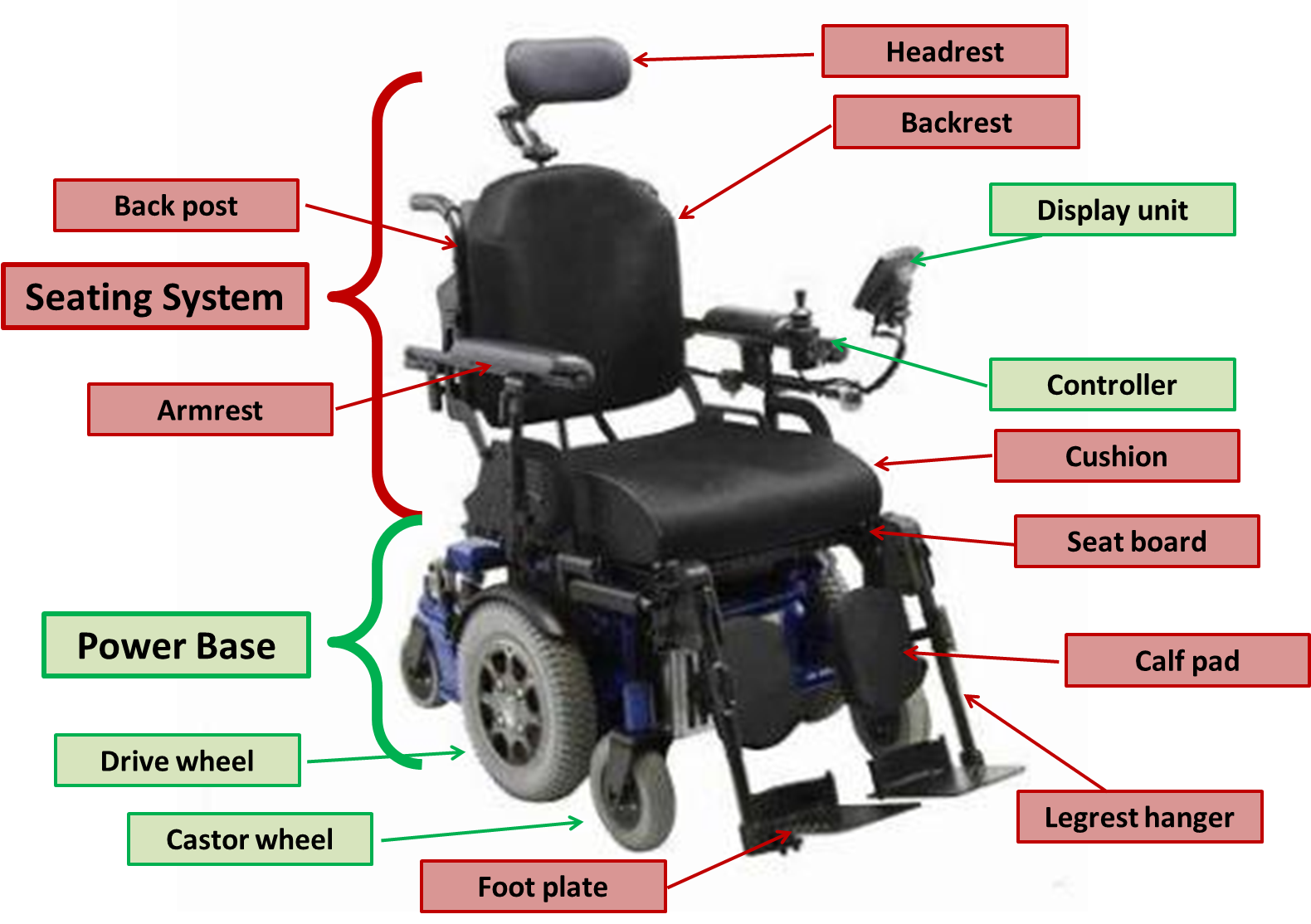

Components of a power wheelchair

A typical PWC has a power base, seating system and may have additional equipment essential to the client. The seating system refers to the components of the chair which directly contact and support the client while the power base relates to the components of the chair directly relating to the mobility function. Auxiliary client equipment has a specific function and typically operates independently from the chair, e.g. phone, drinking system and legbag opener.

The Power Base

The power base includes the frame, drive system, the wheels and the batteries.

The drive system

The drive system includes the controller (input device), various electronic modules, motors and additional associated software and hardware.

The controller

The controller provides the client or carer the means of driving and steering the wheelchair, as well as providing control of power seating functions such as seat tilt (where fitted). The controller may be:

- Proportional: including most joystick-type controllers and attendant controls. Proportional controllers give smoothly variable speed and direction.

- Non-proportional or digital: including digital switches such as ‘sip and puff’ systems or a head array. Non-proportional controls typically provide directional control but limited capacity to vary speed.

A PWC uses ‘modules’ to control the drive response to user commands with relation to, speed, acceleration, deceleration and tremor dampening, or to provide additional functionality such as infrared or bluetooth connectivity:

- The control module sends inputs from controllers to the motors and power seating mechanisms, provides feedback to user and allows performance adjustment through programming

- The power module directs energy to the motor and to control steering

- A multi-actuator module may be needed for multiple power seating functions

- Specialty control input modules and enhanced display units may be required for specialty control device

- An environmental control module can allow the wheelchair controller to communicate with appliances in the client’s home.

- Other modules have also been developed to provide key functions to the chair, such as the bluetooth module. Modules available vary with PWC manufacturer, and some are available from third party manufacturers.

The PWC’s motors are responsible for driving and steering the chair:

- The motors need to be able to propel the occupied chair in the most challenging terrain (up steep hills) that the client will normally encounter

- A motor’s torque is a measure of its ability to do strong work (like driving uphill) while a motor’s speed is a measure how fast it will drive the chair on flat, smooth terrain. Note that the Australian Government regulates that wheelchairs must not be able to be driven faster than 10km/h.

Many PWCs include an advanced steering system that assist in maintain a straight course on cambered surfaces. Clients with poor hand function, or who use non-proportional control devices such as ‘sip and puff’ or chin control will benefit from a course correction system on sloped pavement and kerb ramps.

Some PWC power bases are fitted with manually operated wheel locks that can be applied to prevent rolling when the chair’s motors are disengaged. Motors for PWCs will also have automatically applied braking systems to prevent uncontrolled rolling when there is no control input.

Drive wheel configuration is named according to the drive wheel location in relation the user’s centre of gravity. The following terminologies on drive wheel are used in Australia. The pros and cons may vary depending on the PWC models and user needs:

FWD - Front wheel drive

- May ‘fishtail’ when driving at speed

- Has better traction on declines than inclines

- Wheelchair turns about the front

- Rear portion of wheelchair swings wide when turning

- No clearance required in front of the chair to turn

- Allows 90 degree thigh to knee angle

- Reversing is not intuitive

RWD - Rear wheel drive

- Good directional stability

- Has better traction on inclines than declines

- Wheelchair turns about the rear (like a car)

- Front portion of wheelchair swings wide when turning

- No clearance required behind chair to turn

- Foot positioning limited by castor swing interference

MWD or CWD - Mid wheel drive or centre wheel drive

- Traction about equal for up and down inclines

- Has four castors for stability (two forwards, to rearwards)

- Intuitive to manoeuvre

- Chair turns about the centre of the power base

- Small footprint and turning radius

- Client may experience a pitching action

- Comparatively rougher ride on uneven terrain

- Allows 90 degree thigh to knee angle

Wheels

Drive wheel and castor size should be selected to suit the environments in which the client will typically be driving.

Drive wheel:

A chair with large diameter drive wheels will climb small lips and ledges more easily and be less affected by crossing cracks in pavement. Wider drive wheels willnot sink as deeply in soft terrain and will have greater traction on loose ground and rough terrain and be less affected by driving along cracks. However, wide tyres can increase chair width which may affect access, and can damage carpet.

Castors:

Castor size and width influence manoeuvrability and kerb climbing. Castor size may also place restrictions upon leg positioning for RWD, MWD and CWD chairs, depending on the swivel diameter of the castors.

Suspension, kerb climbing and stability technologies:

Ongoing design and technology allows the client to have improved ride and control in outdoor terrains.

Stability is particularly important for chin control and mini-joystick users who have difficulty maintaining control on uneven terrain. Where feasible it is good to trial equipment in as many environments as are applicable to the user’s expected use (particularly over rough terrain where this is relevant).

Battery

To maximise battery life, chairs should be put on overnight charge after each day of use and either kept on charge or disconnected if the chair is not to be used for an extended period of time.

- Battery capacity should be adequate for the demands of the user and their environment.

- Sealed or gel cell batteries are required for airline transport and travel. Many airlines will require that batteries be physically disconnected prior to stowage. Note: this feature may not be supplied as standard, and may not be an option, depending on the wheelchair manufacturer. Clients who intend to have their chair transported by air, at any point, should consider airline requirements during prescription.

The Seating System

The ‘Seating System’ includes all of the components of the PWC which directly support the client, such as the cushion, backrest, armrests, legrests, headrest and any additional postural supports which are mounted to the chair. These components are introduced in Module 7 and Module 8. Unlike the power base, there is often significant scope for the use of third party seating componentsto best achieve the clinical objectives of seating. The selection of seating components should be based on a thoroughassessment of posture and pressure as described in Module 7 and Module 8. Seating systems in PWCs typically have scope for adjustment of the seat width and depth and other basic seating dimensions.

The seating system may also incorporate power seating functions to provide client and carers with additional capacity to control posture, manage pressure and enhance function. When using power seating functions it is important to ensure that the client can control the seat functions throughout the range of body position and is able to return to the initial posture after using power seating functions.

Example

A client with reduced upper arm function who drives with a manual joystick may not be able to overcome gravity when in tilt to return the chair to level, in this case limits can be placed on the degree of tilt that the chair is able to achieve.

It is prudent to keep the system as simple as possible, without compromising the high priority seating and wheeled mobility goals. Increased complexity in the system increases the need for client and carer training, and also increases operational complexity, equipment maintenance and future repairs. Compromises must be discussed case by case with the client during the process of prescription.Possible power seating functions include tilt-in-space, seat elevation, backrest recline and legrest elevation. Some PWCs also use a combination of power seating functions to effectively stand the client upright.

Tilt-in-space: the seat angle rotates around a pivot point to raise or lower the front of the seat without changing the seat-to-back angle. Tilt-in-space typically allows seating angles from -5° (front of the seat a little lower than the rear) to 65° (backward).

- ‘Weight-shift tilt’ moves the seat on the power base during tilting so that the balance of the chair as a whole remains unaltered, whereas a ‘fixed pivot’ tilt-in-space seating function requires a longer wheel base to maintain stability

- Tilt-in-spacecan be an effective strategy for pressure management. See Module 8.

- A tilt-in-space system uses gravity to improve posture, field of vision, pelvic stability and body positioning. See Module 7.

- A small degree of tilt-in-space adjustment can allow the user to optimise balance and stability in activities such as negotiating kerb ramps and steep descents.

- Tilt-in-space improves access to outdoor terrain and entry to vehicles by allowing adjustment of the ground-to-foot support clearance.

Seat elevation: the seating system can be lowered or raised relative to the floor height to improve transfer, functional reach and social interaction.

- Most chairs with seat elevation will have their forward speed limited when the seat is elevated

- Wheelchair manufacturers are aware that increases in seat elevation reduces chair stability and have taken measures to manage this risk.

- Power backrest recline: The power recline system changes the seat-to-back support angle. Ensure that the client has the muscle length and joint flexibility to assume these changes in angle,

- The basic power recline pivots the backrest on the seat which can cause some sliding of the backrest against the body during recline, because the pivot of the backrest is not aligned with the hip joints. Anti-shear recline systems are designed to minimise this sliding movement

- Power tilt can be used with power recline to enhance pressure and posture management

- When using a combination of seat tilt and backrest recline it is important for the client to correctly sequence these operations to avoid being pushed forward on the seat, as follows:

- When going back: tilt first, then recline backrest.

- When regaining an upright position: backrest up and then un-tilt.

Legrest elevation:

The legrest elevation system changes the seat to leg rest angle. It is important that the client has the muscle length and joint flexibility to assume these changes in angle, in this case the sequencing for power functions is as follows:

- When going back: tilt first, then recline backrest, then elevate legs.

- When regaining an upright position: legrests down, backrest up, and then un-tilt.

The legrest elevation mechanism should ideally pivot as close as possible to the axis of the knee joints to reduce displacement that will cause shear or raise the knees compromising pressure management. Anti-shear legrest elevation systems are designed to move the foot supports with the body to avoid these undesirable outcomes. Ensure that legrest elevation system include sufficient calf support for the extended position.

Power seating functions working together:

When multiple power seating functions are to be used together it is recommended that they are assessed and prescribed together with a customised or synchronised power seating program (one input controlling several seating functions).

The possible applications include:

- Improved pressure management

- A change in posture for rest, or enhanced functional activities such as self-catheterisation

- Reduced need for attendant care

- Management of orthostatic hypotension

- Pain management

- Oedema management- elevating the legs above the heart

- Improvement to breathing capacity.

References

- Denison I, Gayton D. Power wheelchairs: a new definition. [Internet]. Assistive Technology & Seating Service Vancouver Coastal Health; 2006 [cited Oct 2015]. Available from: http://www.assistive-technology.ca/studies/scin.pdf.

- Rehabilitation Engineering & Assistive Technology Society of North America (RESNA). RESNA position on the application of tilt, recline and elevating legrests for wheelchairs. [Internet]. RESNA; 2008 [cited Oct 2015]. Available from: http://www.rstce.pitt.edu/RSTCE_Resources/Resna_Position_on_Tilt_Recline_Elevat_Legrest.pdf

- Queensland Spinal Cord Injury Service. Powerdrive wheelchair features. [Internet]. Queensland Spinal Cord Injury Service: 2015 [cited Oct 2015]. Available from: https://www.health.qld.gov.au/qscis/documents/pdwc-features.pdf

Be systematic: Identifying key issues for appropriate power wheelchair prescription

1. Medical diagnosis

The level of injury may dictate features and accessories of the power wheelchair that the client requires. Clients with an incomplete spinal cord injury may present with asymmetrical head control or upper limb function that will alter the selection of power wheelchair options. Therapists should understand the effects of co-morbidities and other medical conditions on functional abilities e.g. acquired brain injury, arthritis, shoulders and upper limb injuries.

A general guide to seating requirements for clients with a complete spinal cord injury

Thoracic/Lumbar/Sacral-level injuries, T1 and below

- Manual wheelchair is usually the initial primary mobility. PWC may be considered with other co-morbidities, overuse syndrome or injuries (refer to Module 9).

Lower cervical-level C7-C8 injuries

- Clients able to drive with standard joystick. This client group may elect to use the PWC as the primary mobility aid over a manual wheelchair. Factors such as age, concurrent injuries, social support and environment will influence the decision.

Lower cervical-level C6 injuries

- Clients able to drive with adapted or standard joystick

Lower cervical-level C5 injuries

- Clients able to master driving with an adapted joystick or utilises a mobile arm support over the joystick

- Custom armrests and hand supports may be required to allow client use of a hand controller

High cervical-level C4 injuries

- Clients able to drive a PWC with chin control

- Functional capacity similar to C1-C3 but may not require respiratory aids at discharge

- Mouth sticks are used for accessing other controls and keyboards

- Postural stability and wheelchair tray set up is vital for the client to access these aids

High cervical-level C1-C3 injuries

- Requires chin control devices, power tilt-in-space seating function and custom wheelchair mount for a respiratory ventilator

- Depending of the client’s ability to utilise the neck muscles for their head control, a chin control device will most likely be used. Other speciality controls devices including sip and puff and head control device such as head array, switches or ‘mini–joy’ can be trialled. A ‘sip and puff’ control device is used for clients who are able to control breathing but have poor control of head and neck position

- Ventilators and batteries, suction equipment and manual ventilation bag are required to be carried on the power wheelchair

- Clients who have a phrenic nerve paced diaphragm usually require the transmitter to be secured to the wheelchair

2. Surgical history

Take note of any surgical or orthopaedic factors that may restrict the range of joint movement and can compromise the client’s ability to operate control devices or rule out the use of power backrest recline or legrest elevation.

3. Upper limb pain

“Upper limb pain and injury are highly prevalent in people with spinal cord injury, and the consequences are significant”.1

The most common types of upper limb pain and injury experienced by clients with a SCI are8 :

- Wrist and carpal tunnel syndrome

- Elbow

- Shoulder pain, and

- Rotator cuff injury.

In the PVA guidelines, recommendations relating to seating and power wheelchair interventions include:

- PVA Recommendation #6:

- With high-risk patients, evaluate and discuss the pros and cons of changing to a power wheelchair system as a way to prevent repetitive injuries.

- PVA Recommendation #11:

- Promote an appropriate seated posture and stabilisation relative to balance and stability needs.

- PVA Recommendation #12:

- For individuals with upper limb paralysis and / or pain, appropriately position the upper limb in bed and in a mobility device. The following principles should be followed:

- - Avoid direct pressure on the shoulder

- - Provide support to the upper limb at all points

- - when the individual is in supine, position the upper limb in abduction and external rotation on a regular basis, and

- - Avoid pulling on the arm when positioning individuals.

- PVA Recommendation #13:

- Provide seating elevation or possibly a standing position to individuals with SCI who use power wheelchairs and have arm function.

- PVA Recommendation #34:

- Encourage manual wheelchair users with chronic upper limb pain to seriously consider use of power wheelchair.

4. Neck pain

Clients with high lesion spinal cord injury may experience neck pain and discomfort. The use of tilt-in-space power seating function can provide restful support options for the head and neck muscles.

Neck pain can derive from poor posture associated with the awkward use of typical joysticks and chin control devices. A review of the clients seating and driving posture may be required which may result in the provision of more appropriate neck and upper limb support. Specialty control devices may be considered to allow the client to operate the PWC while maintaining optimal skeletal alignment.

5. Pressure injuries

Power seating functions are one of the intervention strategies described in Module 8, and are useful for clients who are unable to perform an effective weight-shift.2

6. Bladder management

Power seating functions such as seat elevation and backrest recline can facilitate the client to perform transfers to the toilet or to perform self-catheterisation in the wheelchair. Assessment should be conducted with supervision of a continence nurse and a physiotherapist or occupational therapist.

7. Weight gain or loss

Weight loss or gain is an indication for an assessment to resize or make adjustments to the seating system. For the client who tends to fluctuate in weight, adjustments to seat width and depth are available in many seating systems with a power base type of PWC. This selection must be considered in new powered wheelchair prescription.

8. Psychosocial and carers issues

For a new user, learning to drive a PWC requires a range of skills:

- Cognition and ability to learn and retain new skills

- Perceptual skills, such as motor planning and visual spatial orientation

- Communication skills, interpersonal and intrapersonal skills

- Judgement and safety awareness.

The client’s self-image and own preferences can influence the client’s decision to accept or reject a potential PWC. Some manual wheelchair users may feel that they are ‘giving in’, deteriorating or becoming more dependent with the idea of a PWC. This transition requires practical input and psychological adjustment. Several PWC trials or short term loans can allow the client to assess progress with pain management and functional capacities before a decision is made for a PWC or power add-on prescription.

Clients who live in residential care, independent living units or group homes often have many care staff, inexperienced or poorly educated carers. Ease of operation, clear labelling or familiarity of commonly used electronics or wheelchair modules should be considered in the power wheelchair selection. Keep the system as simple as possible without compromising the key seating and mobility goals. Discuss the pros and cons, ‘trade-offs’ with the client and facility supervisors.

9. Functional tasks

Explore and discuss with the client the features of the seating and PWC required to carry out their activities of daily living.

When reviewing functional tasks consider:

- The type of armrest required for transfers

- Resting position in wheelchair using power seating functions

- Leisure activities

- Employment

- Carer duties

- Voluntary work, and

- Community participation.

For clients with a high lesion spinal cord injury, options and accessories in power wheelchairs should facilitate these essential functions:

- Head or hand control: selection and adaptations to control devices and head or arm supports

- Vision: provide adequate head support and vision alignment to operate display, select appropriate enhanced display unit

- Feeding and other in-chair tasks: wheelchair trays options and setup for equipment such as mouth sticks, phones, tablets and other technology.

10. Environmental context

As wheeled mobility impacts on all aspects of a client’s daily activities and life roles, investigate the area around the home, work, transport vehicles, shopping areas and other leisure activity environments for factors that will influence PWC interventions.

For the first time user, it is important to ask the client the activities and roles that they wish to participate in following discharge from rehabilitation. Liaise with the nursing staff and allied health staff about the appropriate wheelchair options and accessories in order for the client to carry out functional tasks in the wheelchair post-discharge, such as:

- Educational or vocational activities: appropriate features for the wheelchair such as electronic modules, power seating functions, interface with computers, and

- Leisure and social activities: select the drive wheel configuration for optimal wheelchair performance.

Community clients usually have established their home environment to maximise their functional abilities. Thus, any changes to the PWC dimension and set up should be discussed openly and thoroughly with the client. A trial should be conducted at home where possible.

Selection of PWC options includes:

- Wheelbase configuration: influenced by indoor circulation space and client preference

- Drive wheel size: influenced by likely outdoor terrain

- Battery size: determined by distance needed to travel between recharging

- Power seating functions: influenced by a variety of factors including pressure care, accessibility, comfort (funding options may vary with clinical need).

11. Transportation

Considerations relating to transport are important in determining the wheelchair features. Consider the following aspects:

- Whether the client is a driver or passenger in a motor vehicle

- The type of vehicles being used

- The gradient of the access ramp – for mid-wheel or centre-wheel drive PWC. Test the transition from the ground to ramp or incline to ensure the drive wheels have good traction

- Suitability of wheelchair loading ramps or platforms for the trial wheelchair - weight capacity, dimensions and gradients

- Tie down points, docking systems and sufficient head support must be considered for clients who sit in their wheelchair while travelling in a vehicle

- Crash worthiness of the PWC

- The overall wheelchair dimensions, width, length and height are particularly important when entering and exiting the vehicle - the selection of a PWC with very low seat-to-floor height (with power seat elevation) enables many tall clients access to a wider range or transport vehicles, and

- Manoeuvrability if travelling in public transport such as buses and trains.

12. Existing seating and wheeled mobility limitations

A detailed record of the current mobility system is often the baseline for all wheelchair assessments and interventions. Investigate the problems identified and note the essential features of the components in the PWC required.

References

- Preservation of upper limb function following spinal cord injury: a clinical practice guideline for health-care professionals’, Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine, Paralyzed Veterans of America, 2005 Apr. Accessed 02-05-2024. Available from: https://pva.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/cpg_upperlimb.pdf

- ‘Pressure injury prevention and treatment following spinal cord injury.’ “Recommendation 30.2:” Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine, 2000 Aug (reviewed 2005), published by Paralyzed Veterans of America

- Clarke, T., 2015. Transportation of people seated in wheelchairs. Independent Living Centre WA. Accessed online: 07/05/21. Available from: https://www.indigosolutions.org.au/docs/default-source/fact-sheets/mobility-transport/vehicle-transport/a-guide-to-transporting-people-seated-in-wheelchairs.pdf

- Transport for NSW Motorised wheelchairs and mobility scooters. [Internet]. Transport for NSW; 2024 [cited May 2024]. Available: https://www.transport.nsw.gov.au/roadsafety/pedestrians/mobility-scooters

Work as a team

Wheelchair suppliers have the most up to date PWC product knowledge, including technical details and software capabilities. Suppliers have a valuable role in the PWC assessment, trial, and prescription and provision process.

Consult with the client, carer and suppliers to select the most appropriate PWC device for the client. It is vital that the clinician clearly states the desired seating and mobility goals and the conditions of use to the supplier so that appropriate technologies and PWC configuration can be selected for the trial.

Together with the supplier, explore options and explain ‘trade-offs’ to the client.

A detailed PWC specification and the conditions of driving enable the supplier to configure the seating system and program the PWC for the client’s individual requirements.

Many carers are responsible for the daily operations and regular maintenance of the PWC, such as pushing the PWC to a storage area at night, charging batteries and maintaining tyre inflation. Instructions should be given to the carers.

Formulate trials

- The trial wheelchair seating should be set up to the correct ‘size’ and ‘shape’ for the client

- The trial PWC should have the driving program customised to the user’s driving skill level, activities and environmental conditions

- For a first time user, start by teaching the client how to drive the wheelchair. Once the client is competent, introduce power seating functions or other interface technology gradually. Wheelchair training is part of the prescription process

- Trials should be long enough to simulate the duration of typical daily activities around the home, work and community outings

- A set ‘obstacle course’ for indoor and outdoor environment can be used if trials cannot be conducted in the home environment. This may include a specified route around the hospital that involves ramps, pedestrian crossings, kerb ramps, gutters, uneven terrain, carpet, tight circulation space and doorways. When comparing different chairs use a consistent test route

- The clinician should list the trial conditions and ask for feedback in a systematic way using a table format. It is particularly useful when documenting clinical rationale and funding applications

Persevere!!

Wheelchair seating is a complex process; do not be discouraged if the first chair or configuration trialled is not completely satisfactory. While the full configuration may not be right, it is likely that observation and consideration of the trial will give insight as to what elements are working, and which need to be reconsidered.

Do not give up too quickly! While there are rare instances where it may not be possible to achieve outstanding results in all four seating clinical objectives as well as meeting all of a client’s seating goals, in general patience and steady progress will yield a good seating result.

References

- Axelson P, Minkel J, Perr A, Yamada D. The powered wheelchair training guide. [Internet]. PAX Press; 2002 [cited Oct 2015]. Available from https://www.yumpu.com/en/document/read/11403491/the-powered-wheelchair-training-guide-wheelchairnet

- Nilsson L, Durkin J. Assessment of learning powered mobility use - applying grounded theory to occupational performance. Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development [Internet]. 2014 [cited Oct 2015]; 51 (6): 963-974. Available from: https://www.rehab.research.va.gov/jour/2014/516/pdf/JRRD-2013-11-0237.pdf

- Durkin J, Nilsson L. ALP – Assessment of learning powered mobility use: Facilitating strategies [Internet]. US Department of Veterans Affairs; 2014 [cited May 2024]. Available from: https://www.rehab.research.va.gov/jour/2014/516/pdf/jrrd-2013-11-0237appn2.pdf

Key concepts in this module

- Good power mobility provides the client with postural support, pressure care, functional abilities and access to community participation

- When assessing for PWC, each component of the power wheelchair plays a part in meeting the client’s complex needs. A systematic approach in selecting and recording the components is needed

- A PWC can be operated by small movements of any body part such as the hand, finger digit, shoulder, foot, head, lips and chin for a client with a high level of motor dysfunction. A precise seating posture and positioning is vital for the client to operate the PWC with controls devices effectively. Refer to Module 7

- There are often compromises with selecting the appropriate seating, wheel configuration in powered wheelchair to meet the client’s clinical, functional and environmental needs. Clients should be given the pros and cons of the suitable options and relevant trials.

- Good cognitive skill is required to use and navigate the options and settings of a full function wheelchair controller.

- PWC customisation and wheelchair training must be provided in order to achieve a successful outcome.

Case study: Katherine

Case study questions

- List the medical status and physical concerns that Katherine has and the possible requirement of the new PWC to address these issues.

- List the functional task that Katherine performs in her wheelchair. How would these tasks influence on the selection of the wheelchair components and accessories?

- What are the social and environmental factors that will influence on the components selection in her PWC?

Case study answers

- List the medical status and physical concerns that Katherine has and the possible requirement of the new power wheelchair to address these issues.

- As a person with C5/6 tetraplegia, Katherine is dependant in power wheelchair with modified joystick and switches for mobility.

- A postural assessment will indicate the cause of neck pain. Possible solutions may include power tilt-in-space to alter neck posture and adequately supports for head and upper limbs.

- Having had a history of a stage 3 pressure injury, Katherine should consider a power tilt-in-space seating function for independent weight shift as part of pressure injury prevention.

- List the functional tasks that Katherine performs in her wheelchair. How would these tasks influence the selection of the wheelchair components and accessories?

- In order for Katherine to empty the catheter bag, she will need an accessible bag hook on the front of the wheelchair and suitable backrest push handle to maintain balance during this process.

- Katherine uses the computer for domestic planning and may take on study at TAFE. Consider controller modules that allow the control device to interface with the computer and other electronic device such as PDA. A wheelchair tray will also be useful.

- Katherine travels to the school in her wheelchair daily with her kids. Motor and battery sizes should be sufficient to cover the distance she travels daily.

- What are the social and environmental factors that will influence on the components selection in her power wheelchair?

- Katherine travels to the movies and luncheons in a wheelchair accessible taxi. The new wheelchair dimension in width, length and height should fit inside the wheelchair taxi. Tie down points must be provided.

- Katherine’s social activities are manly indoor such as restaurant and shopping centres. Manoeuvrability such as small turning radius, seat to floor height would be a higher priority than travelling in rough terrain.

Printed: May 5, 2024 2:25 am