This project sought to improve the effectiveness of the Transitional Aged Care Program (TACP) by unifying and clarifying the governance and underlying philosophy across all teams, improving communication, building case management capacity and facilitating meaningful community connectedness.

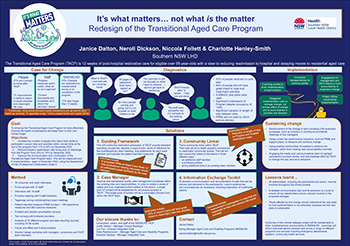

View a poster from the Centre for Healthcare Redesign graduation April 2022.

Aim

- Increase the number of people who report their ability to participate in life roles and community activities at the end of the program from 11% to 30% by December 2022.

- Reduce the TACP hospital readmission rate during and on discharge from 23% to 19% by December 2022.

- Improve communication and coordination measured by the Assessment of Inter-Professional Collaboration Scale II by December 2022.1

Benefits

Benefits for the person

- Through improved communication, the person understands the intention of the program and how to make the best of it.

- An improvement in their ability to return to meaningful life roles and community activities.

- Feeling a sense of control as individual clinical services are coordinated to work toward what matters to the person.

- Able to live at home longer with or without supports.

Benefits for staff

- Staff have a clear understanding of the philosophy of the program, have common governance procedures, and are adequately supported and trained.

- Staff have a sense of achievement when people complete the program having fulfilled their own goals.

- Improvement in staff morale and productivity resulting from collaborative inter-professional teamwork.

Benefit to the health care system

- A 4% reduction in the hospital readmission rate by December 2022 and continuing reductions thereafter.

- More defined support plans, maximised service utilisation and reduced waste.

Background

The TACP program is 12 weeks of post-hospital community-based rehabilitation, delivered by five multidisciplinary teams across Southern NSW Local Health District. The program aims to reduce readmission to hospital and prevent early admission to residential aged care by supporting older people to stay longer in their own homes.

People and staff

- Services offered were determined by the staffing profile at each site rather than being based them on the person’s identified needs.

- People reported there was a “lack of focus on what I wanted to achieve”.2 This fragmented the interventions, leaving people having to retell their story to numerous clinicians, causing unnecessary repetition, frustration and stress.

- In 2021:

- 23% of TACP people were readmitted to hospital during or on completion of the program

- 37% of people did not remain at home.3

- 33.9% of people stayed on the program longer than the intended 12 weeks as a result of unmet goals.3

- People reported only a 7% improvement in their ability to return to social activities and meaningful life roles on completing the program.4

- Despite evidence linking reduced community connectedness to worsening health, there was no organisational provision in the TACP for connecting the person with, or preparing them for, community activities that were meaningful to them. 64% of support plans did not include goals linking the person to community connectedness.5

- Information about the program was presented to and sought from clients in indigestible packages. People, including staff, reported feeling confused and overwhelmed by the 46 pages of onboarding paperwork they were faced with, when all they wanted was to go home (consumer interview 2021). In addition, staff viewed the current patient-reported measure tools as a burden on the client and deemed them as not useful in informing support plans (consumer and staff interviews 2021).

- Care planning often overlooked the assessment for, and provision of, psychological help.5

Health care system

- The program budget sat in surplus, despite operating at 110% occupancy during 2020.6

- Despite LHD attempts for consistency of practice, there was no unifying, agreed philosophy or standard governance.

Implementation

Extensive research was conducted through the diagnostics, solutions and implementation phases of the redesign process. Activities included

- Literature reviews

- 18 interviews with individual staff members

- 32 interviews with people and their carers

- Medical record and data audits;

- Multiple day long workshops with TACP people, managers, program coordinators and team members.

- Continuous input was sought from the project’s steering and advisory committees, both of which included previous TACP people or age appropriate members.

- As a result of these activities the following four solutions were generated and will be tested from Feb 2022-Dec 2022.

Solution 1: Guiding framework

- Develop local applications of the Commonwealth Transition Care Guidelines 2019 (updated March 2022) to ensure program equity and delivery is in accordance with people’s needs.7

- Develop a model for comprehensive, supported self-management plans, understandable to people, which will be used to guide team meetings and be reviewed and modified as the person’s needs change.

- Select patient-reported measures relevant to the program’s population and valued by the staff as being useful to improve the service.

- Develop a system to ensure resources allocated to the program are used within the program, rather than being diverted to other services.

Solution 2: Revised case manager role

- Develop a clinician case management role in line with current best practice.

- Case managers will provide a single point of contact for each person on the program and develop, with the person, a support plan to be presented to the team.

- Case managers will be supported by training, mentoring and a duty statement.

- The case manager will ensure comprehensive assessment and reviews are completed, and that the person’s needs are addressed.

Solution 3: Community linker

- Trial a community linkers within the TACP teams. Their task will be to foster people’s connections to meaningful community activity. The trial will add community linkers to the teams in three different ways: an additional staff member, a brokered position and giving additional time to an existing team member.

- All three trials will be tested and measured using a validated tool, performance and outcome data.

Solution 4: Information exchange toolkit

- Develop an information exchange toolkit that will improve and support communication with people enrolled in TACP and their carers.

- The toolkit will clearly establish mutual expectations of the program, adjusts communication methods and collaboration style based on individual needs and preferences.

Program operation

After implementing the four solutions, the program’s operation will be as follows.

- The case manager develops a close professional relationship with the person, providing a single point of contact, supervising the person’s progress throughout the 12-week program.

- The case manager progressively, and in close consultation with the person, creates a flexible, personalised support plan. The plan would cover the person’s: medical needs, psychological support, and connection with meaningful community activities through the community linker, domestic assistance, collecting and providing official information.

- The case manager advises the team of the person’s changing requirements, with the co-ordinator overseeing the required treatment changes.

- Should the case manager identify the need for psychological support, the social worker in the team will further assess and initiate external psychological intervention.

Status

Implementation – The project is ready for implementation. It is currently being piloted and tested.

Dates

- Start date: April 2021

- Implementation start - Feb 2022

- End date - Dec 2022

Implementation sites

The redesign will be implemented across all five Southern NSW Local Health District TACP teams

- Goulburn

- Eurobodalla

- Cooma

- Queanbeyan

- Bega Valley

Whilst there is staffing variation between teams, the multidisciplinary community health teams may include allied health assistants, enrolled nurses, dietitians, registered nurses, occupational therapists, physiotherapists, speech pathologists and social workers overseen by discipline specific line managers. The TACP brokered provider of non-clinical services will partner with teams throughout the implementation. The Aged Care and Disability Program in Southern NSW Local Health District provides overarching governance.

Partnerships

Centre for Healthcare Redesign

Evaluation

The implementation will be monitored and evaluated. Outcome and process measures for each solution have been adopted.

Solution 1: Guiding framework

Outcome measures

- The improvement in communication and coordination of program teams will be measured by the Assessment of Inter-professional Collaboration Scale which will be collected prior to implementation and again in December 2022.1

- The initial quality audit reporting system process will be repeated in June 2022 to measure the increase in support plans with goals linked to meaningful roles and activities.

Process measures

These measures will be collected and reviewed in the Quality Improvement Data System (QIDS) by the working group and coordinators during implementation and evaluation phases Feb-Dec 2022.

- Monthly reviews of clinical practice Aug-Dec 2022 to ensure inter-professional meetings are based on person’s goals.

- Number of completed patient reported outcome and experience measures at week 6 and week 12 of the program (collected monthly Jan-Dec 2022).

- % completion of supported self-management plans with social or occupational goals (45 files audited on a six-monthly basis June 2021-Dec 2022).

- % adherence to the Consistency of Practice Tool (review conducted monthly Aug-Dec 2022).

- % completion of supported self-management plan within two weeks of admission to the program (collected weekly Aug-Dec 2022).

- Number of staff that have completed orientation to program changes (collected Oct, Nov and Dec 2022).

- Number of interdisciplinary team members and brokered provider attendance at team meetings (collected weekly March-Dec 2022).

Solution 2: Revised case manager role

Outcome measures

- Patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS-29) completed at beginning and end of program to measure the number of people who report their ability to participate in social roles and activities within normal limits at the end of the program.

- 60% of support plans will have goals linked to meaningful roles and activities (TACP QARS audit).

- Unplanned hospital readmission rate reduced to 19% by Dec 2022. (TACP Occupancy Tracking Spreadsheets).

Process measures

These measures will be collected and reviewed in QIDS by the working group and coordinators, during implementation and evaluation phases Feb-Dec 2022.

- Number staff that attend endorsed case management training (collected May, Aug and Nov 2022).

- % completion of supported self-management plan within two weeks of admission to the program (collected weekly from Aug-Dec 2022).

Solution 3: Community linker

Outcome measures

- PROMIS-29 completed at beginning and end of program recorded in QIDS monthly to measure the number of people participating in life roles and social activities that are meaningful to them.

- Rate of unplanned hospital readmission rate collected monthly.

Process measures

These measures will be collected and reviewed in QIDS by the working group and coordinators, during implementation and evaluation phases Feb-Dec 2022.

- Number of people that are engaged with the community linker by week 4 of their program (collected weekly July-Dec 2022).

- Reduction in length of stay and cost of readmission of the program’s people (report run Dec 2021, June 2022 and Dec 2022).

Solution 4: Information exchange toolkit

Outcome measures

- PROMIS-29 will be completed at beginning and completion of program recorded in QIDS monthly to measure the peoples’ improvement in their ability to participate in roles that are meaningful to them and connect with social activities.

- 45 randomly selected files will be audited on a six-monthly basis between June and December 2022 to measure the number of goals linked to meaningful roles and activities.

Process measures

These measures will be collected and reviewed in QIDS by the working group and Coordinators, during implementation and evaluation phases Feb-Dec 2022.

- Number of times the program’s orientation video is viewed by people at first meeting with their case manager.

- Increase number of people completing PROMIS-29 at week 6 and week 12 (collected by coordinators monthly Jan-Dec 2022).

- Number of people that would choose a multimedia platform if it was available (collected monthly Feb-Dec 2022).

Lessons learnt

- All stakeholders must be involved in the initial consultation process because whilst one group, for example middle management, may be easily engaged another group, such as clinicians may not. In the end however, Kotter’s advice that a coalition of support, powerful enough to lead and reinforce the required changes, must be assembled should be followed.8

- A detailed communication plan is crucial as it helps to ensure all key stakeholders remain informed of the proposed changes.

- The altered situation of those affected by the change should be understood so that implementation is not adversely affected.

References

- Glover P, Gray H, Shanmugam S, McFadyen A. Evaluating collaborative practice within community-based integrated health and social care teams: a systematic review of outcome measurement instruments. Journal of Interprofessional Care. 2021;1-15.

- Southern NSW Local Health District. TACP Patient Reported Experience Measures. 2021p. 2020 results.

- Southern NSW Local Health District. TACP Occupancy Tracking Spreadsheets, 2021. 2020 results.

- Southern NSW Local Health District. TACP Patient Reported Measures PROMIS 10 Question 6 responses. 2020.

- Southern NSW Local Health District. QARS TACP Test Audit Results. December 2020.

- Southern NSW Local Health District / Murrumbidgee Local Health District TACP Occupancy Database. 2020.

- Australian Government Department of Health. Transition care Guidelines (updated March 2022). Canberra: Dept. of Health; 2019.

- Kotter J. Why transformation efforts fail. Harvard Business Review. March-April 1995;59-67.

Further reading

- Berntsen G, Strisland F, Malm-Nicolaisen K, et al. The Evidence Base for an Ideal Care Pathway for Frail Multimorbid Elderly: Combined Scoping and Systematic Intervention Review. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2019;21(4):e12517.

- Buljac-Samardzic M, Doekhie K, van Wijngaarden J. Interventions to improve team effectiveness within health care: a systematic review of the past decade. Human Resources for Health. 2020;18(1).

- Ending Loneliness Together in Australia

- Jones A, Jones D. Improving teamwork, trust and safety: An ethnographic study of an interprofessional initiative. Journal of Interprofessional Care. 2010;25(3):175-181.

- Koh,G. Transitional Care from Hospital to Home for Older People. JBI Evidence Summary. 2021

- Lim MH, Eres R, Vasan S. Understanding loneliness in the twenty-first century: an update on correlates, risk factors, and potential solutions. Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology. 2020;55(7):793-810.

- MacInnes J, Billings J, Dima AL, et al. Achieving person-centeredness through technologies supporting integrated care for older people living at home: an integrative review. Journal of Integrated Care. 2021:vol. 29 no. 3, pp 274-294.

- Ogrin R, Cyarto EV, Harrington KD, et al. Loneliness in older age: What is it, why is it happening and what should we do about it in Australia? Australian Journal of Ageing. 2021;40(2):202-7.

- Peltonen J, Leino-Kilpi H, Heikkilä H, et al. Instruments measuring interprofessional collaboration in healthcare – a scoping review. Journal of Interprofessional Care. 2019;34(2):147-161.

- Sempé L, Billings J, Lloyd-Sherlock P. Multidisciplinary interventions for reducing the avoidable displacement from home of frail older people: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2019;9(11):e030687.

Contact

Janice Dalton

Acting Aged Care and Disability Programs Manager

Southern NSW Local Health District

Phone: 0436 852 498

Janice.Dalton@health.nsw.gov.au