The project aims to reduce 28-day mental health readmissions in Western Sydney Local Health District (WSLHD) by identifying the key issues which lead to high readmission rates, and to implement targeted solutions to address these factors. Changes to the admissions, care co-ordination and discharge processes were implemented. Consumer, family and carer input into care planning was emphasised, along with the patient journey from admission to discharge and transition to the community.

View a poster from the Centre for Healthcare Redesign graduation, April 2017.

Aim

Goal

Our goal is to ensure that mental health consumers, their families and caregivers, are better supported and connected in the community post-discharge from an acute mental health facility.

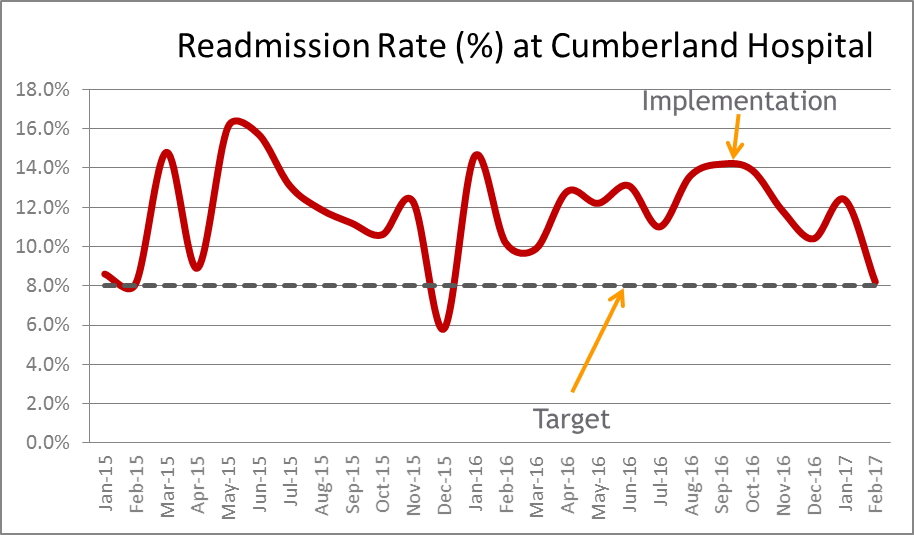

We will be working to reduce the 28-day readmissions rate at Cumberland Hospital from 12% to less than 8% by April 2018 (Source: LHD HIE).

Our Objectives (using the triple aim)

- Improving the patient experience of care by recapturing more nights of patients’ sleep in their own beds. By reducing overnight bed days in hospital due to readmissions by 20% from 545 overnight bed days per month to 437 between 1 July 2017 and 31 December 2017.

- Improving the health of the population by preventing and reducing hospital readmissions. By reducing the average number of readmissions a month from 16 to less than 10 between 1 July 2017 and 31 December 2017.

- Reducing the per capita cost of healthcare for people that are readmitted. By reducing the average length of stay for people that are readmitted from 18 to 14 days between 1 July 2017 and 31 December 2017.

Benefits

The overall benefits of the project include enhanced consumer experiences, improved staff support and morale, and greater efficiency and effectiveness within Mental Health Services to respond to current and future consumer needs.

- Mental health consumers, their families and caregivers will have alternatives to readmission, and be better supported and connected in the community post-discharge from an acute mental health facility assisted by a comprehensive and active wellbeing plan.

- In 2015 there were over 30 readmissions per month across mental health services costing the LHD approximately $6.5M. A 20% reduction in readmissions could save 1000 bed days and $1M per year. In terms of cost, one day in an acute psychiatric facility is comparable to 20 treatment days in the community.

- Secondary benefits include improved service-level key performance indicators including 7-day follow-up targets, and the rate of mental health patients waiting in emergency departments over 24 hours.

Background

Within our mental health service there are a high number of people that are readmitted within 28 days of discharge. The readmission rate in the mental health service has historically sat 3% above the 13% performance target set by the NSW Ministry of Health, which calculates readmissions to any other mental health facility in NSW (Health System Performance Report, 2016). Also, the long term average readmissions rate which measures readmissions back to the same hospital for the past two years was 4% above the 8% peer benchmark rate. This was identified through peer benchmarking within The Health Round Table in 2016.

This equates to over 30 discharged patients being re-admitted to a mental health facility each month, or 1 in 9 people who are discharged are re-admitted (Local data extract). Furthermore, in 2015 within the service there were 6,543 days spent in hospital by patients following a readmission to hospital, costing the mental health service approximately $6.5M. A 20% reduction could save $1.3M and 1,300 readmitted bed days per year.

Readmissions within 28 days of discharge forms part of the Australian National Mental Health Benchmarking project (Callaly et al, 2010). It is described as an indicator of the effectiveness of community care and the organisation’s ability to provide continuous care across programs; it is widely regarded as a broader proxy marker for quality of care (Callaly et al, 2010; Mark et al 2013).

The literature on readmissions describes higher than ideal readmission rates are indicative of fragmented mental health care (Mellesdal et al, 2010). This is seen to impact not only health budgets, but is also associated with poorer patient health outcomes, due to the discomforts associated with readmissions (Callaly et al, 2011). Qualitative analysis has described heavy flow-on effects for patients through to family, carers as well as staff, and clinicians (Duhig et al 2015; Greysen et al, 2016).

There is debate in the literature as to the validity of mental health readmission rates as an indicator of hospital or community performance (Callaly et al, 2011; Mark et al, 2013). The main reasons cited are that the risk factors associated with re-admission such as homelessness, living alone and being unemployed (Oiesvold et al, 2000) are not totally under the control of mental health services. However, it is commonly accepted that readmissions are multifactorially determined covering a range of personal, illness, organisational and community issues (Callaly et al, 2010; Oiesvold et al, 2000). The challenge for services is to identify which readmissions were undesirable and what the variables were, and which are associated with those patients or their care (Callaly et al, 2010). Given that there is a long term variation with our readmission rates within our service compared to that of benchmarked peers, there was value in further examination of this issue.

The redesign methodology provided the foundation for this examination of the issues and the identifying and implementation of the solutions.

Implementation

The solutions implemented include the following three items.

1. Senior Psychiatry led re-admissions process supported by the multidisciplary team

Implementation from Nov-16 to Jun-17

- The Clinical Leader (Senior Psychiatrist) for the unit to lead decision making around the need for admission for people re-presenting to hospital supported by the multidisciplinary team.

- A care pathway developed for people re-presenting to hospital, which describes:

- Allied Health professionals to be involved in the admission process for consumers re-presenting to hospital for admission, as required.

- Psychologists to support admitting doctors by discussing with consumers the psychosocial factors contributing to worsening symptoms, and identifying alternative solutions to admission.

- Alternatives identified include access to Emotional Health Clinic as outpatient within 72 hours with assertive follow-up by community mental health teams.

2. Proactive and predictive flow management between settings

Implementation from Nov-16 to Jun-17

- Discharge planning to commence on admission with goals and objectives collaboratively developed with consumer & carer for the inpatient admission.

- Assertive in-reach from community mental health teams as early in admission with appointments booked for follow-up prior to discharge.

- Community teams make contact with consumers within the first 72 hours of admission.

- Patient flow coordinators are in place and trained in best practice methodology for patient flow, use of journey boards and predictive tools, with twice daily flow meetings with community mental health involvement.

3. Engagement of Consumers and Carers in Care Planning

Implementation from Nov-16 to Jun-17

- Care Planning Meetings: Involvement of carers in care planning and discharge planning meetings. Focus on collaborative and comprehensive care planning with the development of crisis and wellness plans.

- Consumer Representatives: Deployment of consumer representatives in the acute setting to ‘share experiences’, advise consumers of rights and inform of support services.

- Programs for consumers: Provision of educational and therapeutic programs for consumers run by carers and consumers that assist in the development of care and crisis plans.

- Employ a peer support worker in a community mental health team, and redesign the consumer worker inpatient role to provide peer support.

Project status

Implementation - The initiative is currently being implemented at Cumberland Hospital, and is in the pre-implementation phase at Blacktown Hospital.

Project dates

March 2016 – April 2018

Implementation sites

- Western Sydney Local Health District Mental Health Services:

- Cumberland Hospital - Commenced in Paringa acute admissions unit, to be extended into Hainsworth acute admission unit.

- Blacktown Hospital - to be extended to Bungaribee House

Partnership

Centre for Healthcare Redesign

Evaluation

As of April 2017, the project is in implementation phase, and initial observation of collected data suggests positive results, however formal evaluation processes are in development.

Quantitative measures

- Monthly readmission rates utilising source of truth patient administration systems.

- Number of consumer wellbeing plans developed and saved on the electronic medical record.

- Length-of-stay for consumers who are re-admitted.

- Estimated dates of discharge against actual discharge dates.

Qualitative measures

- Structured feedback from consumers, families/carers and staff.

Between November 2016 and February 2017, 11 consumers were diverted from readmissions using the alternate pathway.

As of January 2017, the year to date rate for WSLHD mental health inpatient admissions sat at 10.8%.

Testing and piloting of consumer wellness plans has been completed at Cumberland Hospital, and roll-out has commenced on inpatient wards. Focus groups are being held to evaluate consumer and carer feedback.

Lessons learnt

- To be pro-active in our approach, procrastination did not work. After assimilating the relevant information, we tried to finish every project meeting with making decisions on what needed to be made.

- We found that wrong decisions or mistakes could be salvaged, if discovered early; but delaying the right decisions could not be postponed and came at our own expense.

- When things went wrong, excuses did not work. We had to find an alternative course of action or remedial propositions instead.

- Allocating blame only caused dissention and hostility, searching for solutions brought the team together. Also knowing who you can turn to for help assisted in these situations.

- Being continually open to change.

- Know what resources are available. Sometimes, we found others in other teams and community volunteers were happy to help and assist with the project.

- Know your consumers and know the reasons why you are doing this project and the objectives of the project at hand. This helped with our 30 second grabs.

- That the project schedule is your friend. It was a pain to put together and continually update, but it was a critical tool for the project’s success.

- Continually engaging and communicating with and having the support of our project sponsor, internal and external stakeholders and consumers and carers.

- Having the support of our project sponsor.

Further reading

- Callaly, T., Hyland, M., Trauer, T., Dodd, S., Berk, S. (2010). Readmission to an acute psychiatric unit within 28 days of discharge: identifying those at risk. Australian Health Review(34), 282-285.

- Callaly, T., Trauer, T., Hyland, M., Coombs, T., Berk, M. (2011). An examination of risk factors for readmission to acute adult mental health services within 28 days of discharge in the Australian setting. Australasian Psychiatry, 19(3), 221-225.

- Duhig, M., Gunasekara, I., Patterson, S. (2015). Understanding readmissions to hospital in Australia from the services users' perspective: a qualitative study. Health and Social Care in the Community.

- Greysen, S., Harrison, JD., Kripalani, S., Vasilevskis, E., Robinson, E., Metlay, J., Schnipper, JL., Meltzer, D., Sehgal, N., Ruhnke,

- GW., Williams, MV. (2016). Understanding patient-centred readmission factors: a multi-site mixed methods study. BMJ Quality & Safety Online, 0, 1-9. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004570

- Mark, T., Tomic, KS., Kowlessar, N., Chu, BC., Vandivort-Warren, R., Smith, S. (2013). Hospital readmission among medicaid patients with an index hospitalization for mental and/or substance use disorder. Journal of Behavioural Health Services & Research, 40(2), 207-221.

- Mellesdal, L., Mehlum, L., Wentzel-Larsen, T., Kroken, R., Jorgensen, HA. (2010). Suicide risk and acute psychiatric readmissions: a prospective cohort study. Psychiatric Services, 61(1), 25-31.

- Oiesvold, T., Saarento, O., Sytema, S., Vinding, H., Gostas, G., Lonnerberg, O., Muus, S., Sandlund, M., Hansson, L. (2000). Predictors for readmission risk of new patients: the Nordic Comparative Study on Sectorized Psychiatry. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 101(5), 367-373.

Contact

Clodagh Ross-Hamid

Project Lead

Western Sydney Local Health District

Mental Health Services

clodagh.rosshamid@health.nsw.gov.au